Since December of 2010, I’ve been interviewing authors, editors and others almost weekly on craft every Wednesday for SFFWRTCHT, and one of our regular and favorite question is about Best and Worst Writing Advice. It’s always interesting the answers we get. And after hundreds of guests, only a few repeats, it always amazes me how many different answers we get. In fact, sometimes a repeat guest will answer differently each visit.

Since December of 2010, I’ve been interviewing authors, editors and others almost weekly on craft every Wednesday for SFFWRTCHT, and one of our regular and favorite question is about Best and Worst Writing Advice. It’s always interesting the answers we get. And after hundreds of guests, only a few repeats, it always amazes me how many different answers we get. In fact, sometimes a repeat guest will answer differently each visit.

But what surprises me sometimes are the harsh rejections of mainstays writing rules like “avoid passives,” etc. I think sometimes experienced writers reach a point where old rules seem more limiting than helpful, perhaps. But I still find and believe, as an editor and author both, that those rules have an important role to play in most writer’s development and growth with craft.

There’s another old adage in entertainment that applies as much to publishing as Hollywood. It goes like this: “No one knows everything.”

And while it’s true no one knows everything, you do need to know the boundaries before you break them, and writing rules are a great way to learn those.

For example, passives are a weaker form that when employed exclusively or excessively weaken the storytelling and act as telling, not showing. Once you’ve learned how to construct strong sentences, yes, you can use passives effectively, but in the beginning especially, I think learning to write without them is absolutely important and even essential to success.

Another thing about writing rules is that they often outline pet peeves of various people, and some care about one rule more than others. But the value in knowing them is that they tend to help guide you to a stronger path and stronger prose. And they often identify common weaknesses and missteps writers have taken which have hurt their writing, their success, and the appeal of their work not just to publishers but to readers as well. There are differences between writing fiction and nonfiction, between journalism and fiction, and so on. And sometimes fiction rules are helpful if you’re experienced with another form of writing but inexperienced with fiction, as I was.

There’s another adage that gets trotted out too: “Rules are made to be broken.”

You hear people cite writers like Stephen King or Neil Gaiman who have broken rules. And yes, they have and get away with it. But usually they get away with it because the rules are so imbedded into their process that when they stray from them, they do it with such skill that it just works in ways a lesser writer couldn’t manage. You see, knowing the boundaries so well that they become second nature has advantages, and one of those advantages is that you can later deviate outside them a bit without falling off a cliff.

Let me say it again, knowing the boundaries is necessary before you can risk going outside them. And teaching boundaries is what the writing rules so often taught are for.

As a professional editor of both anthologies and novels, I see people violating the rules all day long. Rarely is it on purpose. Most often it’s because they don’t know the rules or understand how to abide by them. And the result is always sloppier, weaker writer, and a less effectively told tale. ALWAYS. I can’t count how many times a day I have to correct over and over the same errors and explain the same rules. It gets tedious. Sometimes it gets annoying. But it’s the job, and it’s made up for by the pleasure and joy I get in seeing the final polished project overcome these weaknesses and really sparkle and shine.

You can’t be expected to just know everything when starting out. And you won’t learn unless someone takes the time to show you, to explain. So part of my role as editor is to do that for you, gently, but firmly. And I try and do it with a sense of humor, too, to hopefully lessen the sting. But I still have to do it, and you still need to learn the rules.

Just because they seem arbitrary doesn’t mean they are. Just because they can be annoying doesn’t mean you can ignore them.

These rules have developed over decades for good reason. And although they evolve as tastes and grammar and publishing house style guides change, most of them have remained relatively the same for a very long time.

So next time you hear or see your writing hero blow off the rules, don’t take it as an invitation to do so yourself. Your journey is not the same as theirs. In fact, your journey is not identical to anyone’s. Learn the rules, practice them until they become instinct and you can recite them by heart. Learn them until you don’t even remember them anymore, you just do it. Because you’ll be a better writer, that’s what their for. And you’ll be more successful and respected.

And once you have that respect, then you can throw caution to the wind and go crazy. But not before.

For what it’s worth…

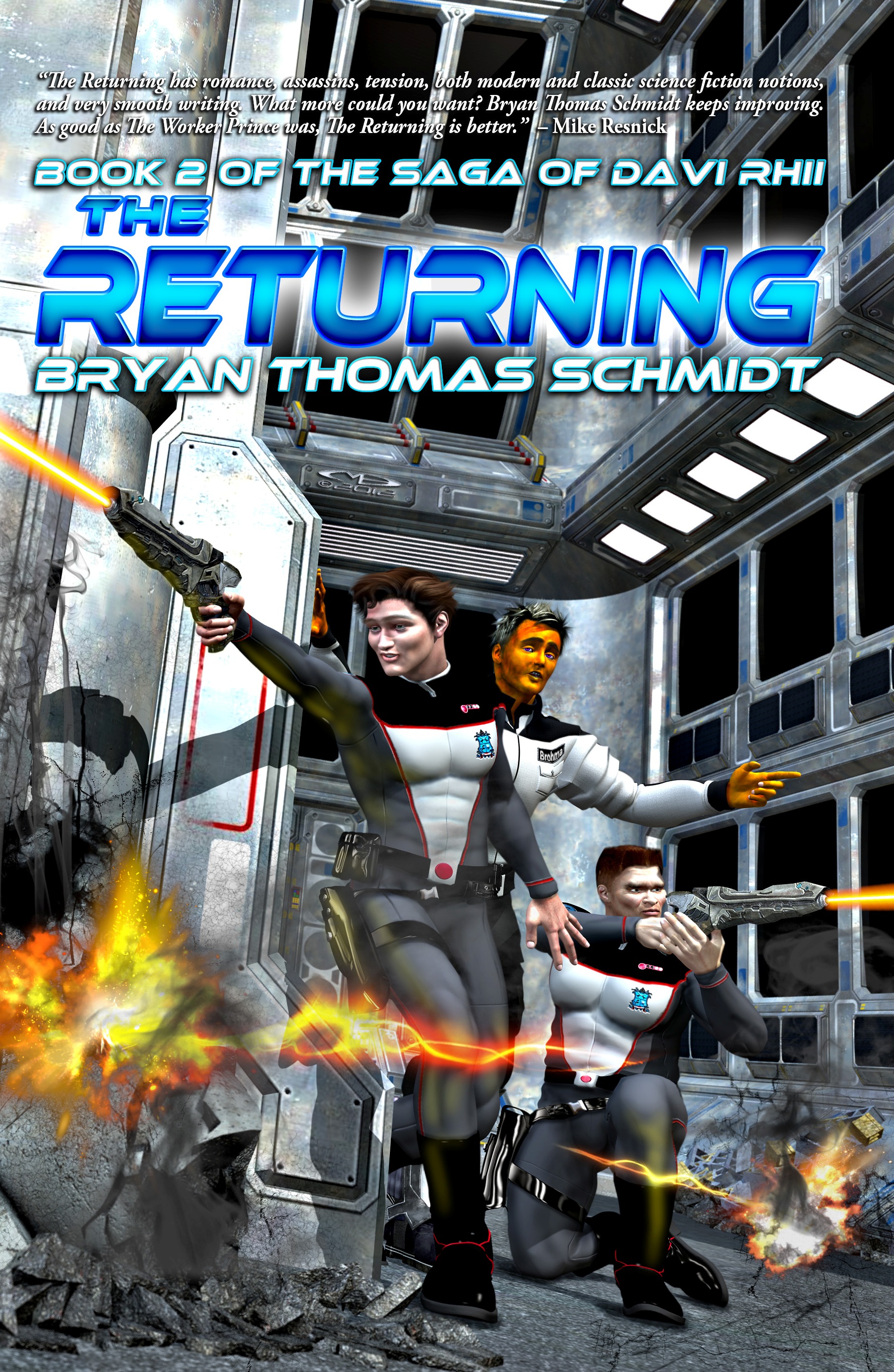

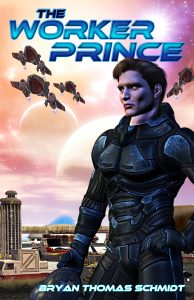

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is an author and editor of adult and children’s speculative fiction. His debut novel, The Worker Prince (2011) received Honorable Mention on Barnes & Noble Book Club’s Year’s Best Science Fiction Releases for 2011. His short stories have appeared in magazines, anthologies and online. He edited the anthologies Space Battles: Full Throttle Space Tales #6 (2012), Beyond The Sun (2013), Raygun Chronicles: Space Opera For a New Age (2013) and coedited Shattered Shields (Bean, 2014) with Jennifer Brozek and is working on Monster Corp., A Red Day, Mission Tomorrow, andGaslamp Terrors, among others. He hosts #sffwrtcht (Science Fiction & Fantasy Writer’s Chat) Wednesdays at 9 pm ET on Twitter.