The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 9: Worldbuilding. It is part of a multipart series. For Part One, click here.

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 9: Worldbuilding. It is part of a multipart series. For Part One, click here.

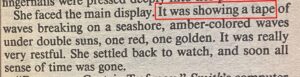

Solar System and Galaxy Relations

The thirteen planets in the star system all varied in size and shape, the outermost and innermost planets being the smallest. Three of the larger planets had several moons. Vertullis had two. While Vertullis, Tertullis, and Legallis alone had atmospheres suitablefor human life, due to Borali scientists’ determina- tion and skill with terraforming, all but one of the system’s planets had been inhabited, though some with populations consisting only of a few workers and mili-tary personnel. The planets revolved around the two suns, Boralis and Charlis, in an unusual orbital pat- tern due to the effect of the twin gravities. Because of the limitations in terraforming science, the four planets nearest to the suns had been surrendered as viable habitats for humans. Of the thirteen planets, Vertullis was the sole planet which had a surface con-taining fifty percent forest, and it had one other distinction. It remained the only planet in the solar system whose native citizens weren’t free. (The Worker Prince, Bryan Thomas Schmidt)

If you are dealing with interplanetary relations—is more than one planet involved? If so what are their relationships physically and spatially and do people travel between them? Are there unique transports like space elevators or quantum tunnels or something? Do they use FTL, Faster Than Light tech? Or do they travel for days and weeks like our current limitations would allow?

As most of us know, one of the key tropes of the science fiction sugenre are starships. They come in all shapes and sizes from planet sized like the Death Star to slightly smaller like Imperial Destroyers down to shuttle craft and tiny fighters like X-Wings or Vipers and everything in between like Battlestars or Cruisers. Some ships are meant for short term travel to and from one locale to another. Others are actually living spaces like cities where hundreds or thousands of people reside and work for years on end. Obviously the size and scope of usage determines the facilities required. And one should take into account the various needs for sleeping, recreation and entertainment, food, medical facilities, waste disposal and personal hygiene, storage, and more. Obviously the longer the ships must function as homes and larger the number of inhabitants, the more concern for supplies, storage, etc. becomes an issue. For every inhabitant, a certain amount of food, water, etc. will need to be regularly used and thus available and stored between ports and stops, with extra reserves for periods of battle, long distance travel, etc. Haircuts, clothing, shoes, grooming, and more are also concerns as well as psychology and counseling, law enforcement or regulations, even criminal detainment, disposal of deceased, sex, and many more. Are they warships or peaceful? Do they have weapons and defenses? What are they? How secure are they? How does this vary according to uses and needs? How does having such items affect the crew compliment and training and roles? So all of this must be considered and weighed carefully in designing your starships according to their purposes and uses.

Solar Systems can be big. Pluto is 4.5 billion miles from the sun at its farthest, while earth is 92.96 million miles. Light can traverse 4.5 billion miles in 5.5 hours. But at current rates, space craft would take years. So to expediate things and make interaction between planets possible, science fiction writers created Faster Than Light travel, FTL for short. This tends to be a minimally defined variant that allows ships to travel between planets in days or hours rather than years. It is a cheat that even some hard science fiction writers employ. Because the practical reality of space travel deals with numbers so high it is hard for writers, let alone readers, to fathom. Not to mention the loss of dramatic tension one experiences when ships must fly toward each other for years before engaging in battle. Whoo hoo, how tense and exciting that is! For creating dramatic tension alone, FTL is really useful. There have been many forms and explanations for it from hyperdrives to warp drives, but all generally come down to the same thing: faster travel between celestial bodies and galaxies.

Solar Systems can be big. Pluto is 4.5 billion miles from the sun at its farthest, while earth is 92.96 million miles. Light can traverse 4.5 billion miles in 5.5 hours. But at current rates, space craft would take years. So to expediate things and make interaction between planets possible, science fiction writers created Faster Than Light travel, FTL for short. This tends to be a minimally defined variant that allows ships to travel between planets in days or hours rather than years. It is a cheat that even some hard science fiction writers employ. Because the practical reality of space travel deals with numbers so high it is hard for writers, let alone readers, to fathom. Not to mention the loss of dramatic tension one experiences when ships must fly toward each other for years before engaging in battle. Whoo hoo, how tense and exciting that is! For creating dramatic tension alone, FTL is really useful. There have been many forms and explanations for it from hyperdrives to warp drives, but all generally come down to the same thing: faster travel between celestial bodies and galaxies.

Hyperspace, in use since 1940s is often depicted as an alternate reality or universe or some sort of subspace existence. Since the science involved is imaginary, you can make assumptions, design mechanisms and assign limits any way you choose as long as you are consistent and plausible. Are there preexisting gates used to enter hyperspace or is it created through some kind of physics or scientific displacement using the special hyperdrive? Are the gravity wells of planets and stars necessary for its success or can it be done anywhere? What role do gravitational fields play? How do you calculate and carry enough fuel and resources to get there and back? Where do you acquire them along the way if needed? Then what about communications? At such high speeds, sound waves are affected. Can they keep up or do you need special communications methods and devices?

And of course, if you can travel between planets, you must address the issue: how are they related to each other? Are they familiar with established relationships that are good or bad? Are they strangers and unknown? Do they share a government or treaties or other common agreements and rules or is it a free for all? Who are their primary populations and what species? What is their primary language and currency? How do any differences get bridged when two different planets interact? How are conflicts resolved and what incompatibilities must be overcome? What is the ongoing history of relations, if any, and what are the issues and obstacles which have arisen and continue to affect ongoing relations?

You must consider separate geography, resources, etc. for each planet. What do they trade? Why? How do their resources, tools, etc. differ? Do they travel across the planet differently? Do they need life support domes? Is gravity modification required? How can different species interact in space that support different life forms?

If your story takes place on Earth or a single planet, on what part of the planet is the story focused? Does the story take your characters to many places or is it concentrated in one area? Knowing this will define the amount and type of research you will need to do. Obviously, knowing one or a few areas really well will be simpler than having to research many and answer all of these questions about them.

Society and Cultures

Doubled, I walk the street. Though we are no longer in the Commander’s compound, there are large houses here also. In front of one of them, a Guardian is mowing the lawn. The lawns are tidy, the facades are gracious, in good repair; they’re like the beautiful pictures they used to print in the magazines about homes and gardens and interior decoration. There is the same absence of people, the same air of being asleep. The street is almost like a museum, or a street in a model town constructed to show the way people used to live. As in those pictures, those museums, those model towns, there are no children. (The Handmaid’s Tale, Marga- ret Atwood)

The next concern is what kind of society and cultures will be present in the setting of your story? If you create aliens or nonhumans, you must first determine how humanoid they are going to be or how different from us? Why? And how did they come to be that way? These questions can be decided by a number of factors: factors about the world on which they will live; practical concerns for language and communication, the relationship they will have with humans, etc.; biological and geographic factors; etc. Since aliens are often what draw many readers to science fiction, they are important, as is the distinction from mythological creatures. Unlike these folkloric beings, aliens are grounded in scientific possibility and so such factors must be careful considered and employed in designing and presenting them. Luckily, the research can be fun.

There are substances other than oxygen which can release energy from sugar and serve biological function, for example. Hydrogen sulfide can replace water in photosynthesis as well. And silicon serves just as well as carbon as a basic building block of life. Your imagination can take you fun but scientifically plausible places if you do the research.

Besides scientific plausibility, however, your aliens must also serve narrative interest by being able to interact with human characters and sometimes even communicate with them and by being intriguing enough to engage reader interest, pique their curiosity or even inspire their fear. Most of the time, this will require sentient beings, but on occasion, when the aliens are meant to serve only as obstacles and antagonists to human characters’ goals and interests, nonsentient alien monsters will do. Don’t forget to consider the evolutionary advantages of the aliens’ unique features. If they don’t need hands, what do they have for limbs? If they can float and don’t need legs, what other features might they need instead? Is genetic engineering involved or is it entirely organic? All of these concerns can lead you in interesting and intriguing directions.

If dealing solely with humans on Earth, what races are involved and what are their relationships to each other? How do they communicate? Do they need translators? What social classes, attitudes, and history do they share and how does that affect their interactions and determine their relationships, etc.? What are the societal roles for each gender? How are LGBT people regarded and treated and what place can they have in society? Are there any limitations placed on people for reasons of class, sexual preference, race, religion or something else? What reasons lie behind any restrictions and what is their history?

There are also environmental factors. If other elements from oxygen and carbon are key elements in our world, what they value, what they eat, what resources they need will all be affected. Their priorities will be influenced accordingly and so will trade, economics, sociocultural interactions, etc. Their goals and values will also reflect this. Food chain, ecology, and economy and the implications of each are key factors as well. Each alien culture will have something distinctive to offer the larger whole toward economy, etc. What that is, how it developed, and what it says about them are important factors to consider as well. Additionally, their evolutionary makeup affects their emotions and memory and learning styles. What if they have a group brain and can share information? How does this group mind affect individualization or emotions or relationships? Is there privacy or none at all? How does this interconnectedness affect their attitude toward and trust of strangers and outsiders? Etc.

While it is a convention of science fiction particularly that humans and aliens are able to understand or speak each other’s languages, in your world are universal translators required or even interpreters? Can they communicate directly or is some form of mind to mind communication used rather than vocal speech? Behavioral and physiological traits can both serve as barriers and increase bonding in relationships with human characters, depending upon how you design them. Thinking these through carefully is key. Also the societal mores, roles, statuses, and laws are factors which will play a role in how aliens and humans think of and about each other and how they interact and will often be key to their relationships and interactions on many levels constantly. What are mating and child bearing and rearing rituals? Are they monogamous or poly? Do they love? Do they form attachments for life or short term or at all? Do they have philosophy or religion? Do they have science or industry? What are the various roles and how are these affected by geography, physiology, beliefs and more?

And did I mention the arts? Do they have fine arts? What about music, drama, painting, sculpting, etc.? What forms to they take? What instruments and mediums are used? What languages? Where are they performed or displayed? What do they look and sound like? How valued are they and by whom in the culture, etc.? A realistic culture will always have such things interwoven into daily life. Loved or hated, characters will take note of them.

“Remember this, son, if you forget everything else. A poet is a musician who can't sing. Words have to find a man's mind before they can touch his heart, and some men's minds are woeful small targets. Music touches their hearts directly no matter how small or stubborn the mind of the man who listens.” (The Name Of The Wind, Patrick Rothfuss)

(To Be Continued Next Week)