The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 13: Editing & Rewriting. It is part 2 of a multi-part series. For Part 1, click here. For part 2, click here.

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 13: Editing & Rewriting. It is part 2 of a multi-part series. For Part 1, click here. For part 2, click here.

Characters, Plot, and Theme

The order in which you review various aspects of craft as you revise is up to you but the one thing this phase has that the writing did not is the advantage of seeing the book as a whole and examining how and if the various parts work well together. In On Writing, Stephen King writes: “Every book—at least one worth reading—is about something. Your job during or after your first draft is to decide what something or somethings yours is about. Your job in the second draft—one of them anyway—is to make that something even more clear. This may necessitate some big changes and revisions. The benefits to you and your reader will be clearer focus and a more unified story.” Things emerge as you write, such as themes which may not have been obvious from the beginning. So now you have the chance to go back through, examine them, and make sure all the elements support and expand the theme in ways that bring out the nuances and add depth.

I generally start with story and structure. So I look at my opening and I ask questions about it as I do.

- Does my story really begin here? Or did I start in the wrong place?

- Is the opening the right pacing and length or did I draw it out too much? Too much description? Too little dialogue and character? Too little emotion?

- Are the story questions clear?

- Is the length of the opening proportional to the rest of the story or is it too elaborate? Too involved?

- Is my opening interesting? Is it compelling?

- Does my opening have enough action?

- Is my opening too flashy such that it effects continuity or does it flow well into what follows?

- Is everything clear so readers know who is talking, where they are, and what’s happening?

After the opening, I start reviewing my plots and subplots and looking at their scene structure, flow, and arcs. I look at the action and conflict. Is something happening or is it static? Does every scene take us somewhere further in plot or character or both? Are the stakes clear? Is what my characters want clear? Will readers care? Do the setups lead to payoffs? Are all the questions being answered? Are they being answered at the right time—the best time to aid tension, pace, and comprehension? Is the information I am giving enough to reveal the story to readers as I see it or did I assume things I failed to impart clearly? How can I make it clearer?

Next, I look at Point of View. Is it consistent—no head hopping? Is the chronology clear and understandable? Am I shifting at the right points or should I rethink? What about too many shifts or too few? Is the tone consistent? Is the character with the most at stake always the point of view character for each scene?

Next, I look at Point of View. Is it consistent—no head hopping? Is the chronology clear and understandable? Am I shifting at the right points or should I rethink? What about too many shifts or too few? Is the tone consistent? Is the character with the most at stake always the point of view character for each scene?

I look at pacing, description and setting. Does the story start fast enough or does it drag? Are individual scenes dramatic and do they start and end at the right spot to keep the tension consistent throughout or do they peter off? Does the payoff at the end of each scene and chapter justify the build up? Did I balance showing and telling? Do I describe too much or too little? What details are missing that might be important? Does each setting add to the tension and tone of the scene in a way that makes it stronger or does it fall flat or detract? Does each scene leave readers feeling something important has happened? Do I use all five senses at least once every other page, if not more? Where can I add more visceral descriptive cues?

If any place bogs down, I look for places to trim the fat and tighten, not only for pacing and tension but also clarity. Too much information can overload readers, while too little can leave them confused. The trick is to find the right balance. Does each section function properly in the story or does anything need to be cut or moved to make the story flow better and stronger overall? This requires some cold efficiency and killing your darlings but the book will always be better for it, every time, and making your book the best it can be is essential. There is no room here for favorite scenes and characters that ultimately serve no purpose but author egos. “I liked writing that” is not enough justification to leave it in. Save it and try and use it in another book or story. Everything that stays here must absolutely belong and add something important or it has to go. Now is the time to reorganize scenes and details. If you reveal too much or too little, reveal it in the wrong order, or omitted important things, this is the time to find and fix it.

Next, I look at characters. Is each major character complete? Are they original or too much of a stereotype? Are they consistent or wishy washy? Are they distinctive or can they be confused with another character? Can anything be added to keep them distinctive? Examine diction and consistency of dialogue and tone—is the character being true to themselves in every word and action they take? Is it believable? What does this character want? What does this character fear? What do they overcome? Does the character grow and change? How? If not, what can be done to fix that. Does each character serve a function in the story or can they be combined or even cut? As editor, I once made a writer cut an entire character and give all her business to another character because she was a minor character who served no real purpose, whereas one of the major characters needed more agency, and so combining them was the best solution. The writer still complains about it to this day, even though she admits it was the best thing for her book. She was later able to go back in and make that character better and more essential to the next book so she could bring her into the story. Ultimately, only keep characters who matter to the outcome of the story. The rest have to go.

Dialogue

I often do a special pass just for dialogue because dialogue is so important. In this, I not only look at character’s diction but the pacing and conciseness of dialogue. I probably trim dialogue and description the most of any parts of any draft. Too much dialogue, too drawn out, not enough action—any of this can be a scene killer and has to go. How can you make the dialogue more dramatic and better paced and less wordy? How can you make even exposition passages feel like they move with action, instead of dragging like info dumps? The trick is to make exposition feel organic and necessary every time by keeping it concise and short. Simple is actually better than complex. Less really is more. Read aloud. Try it out. Do you stumble anywhere? Is it smooth and natural or does it need refining? Are the characters distinctive from each other? Is it clear who is speaking in each case? Characters should sound like individuals, not clones. Listen hard to them and make sure each character has some unique nuanced turns of phrase or styles. Maybe some speak in complete sentences while others talk in spurts and fragments. Some may discuss things directly while others beat around, especially when it comes to emotions. Whatever the case, all dialogue is transactional in nature: it is about an exchange of something useful between two parties, so make sure something happens in every exchange. Is the dialogue accompanied by appropriate actions and descriptive modifiers to show frame of mind, mood, etc.? Most of all, do they all sound like real people?

Ken Rand writes in The Ten Percent Solution: “We don’t just see words when we read. We use other senses. We make mistakes because sometimes the senses we’re using right now to read copy may be dulled, distracted, or otherwise not functioning to capacity. The solution is to employ different senses in a systematic manner during the editing phase, to catch on the next pass errors that escaped the last pass.” Reading aloud not only employs your ears but your tongue, your eyes, and your mind and heart in ways different from just reading silently. You will hear the way things sound, rather than imagining it. You will hear repetition clearly, for example, because you ears picking it up even as your lips read it time and again makes it really pop out. Hearing how the pacing and flow aid the emotional effect of the prose is also invaluable. It is the best way to give you insight into the reader experience you are offering in time to make fixes. You will hear things that sounded complete in your head but are not—not clear, not complete, not as intended. You will notice sentences that seem to run on or end abruptly. Places where transitions between sentences, paragraphs, or chapters seem awkward or abrupt. And places where characters are speaking but it is unclear who is who. These and such more are things you don’t want to overlook, and reading aloud is a great tool to help you find them.

Let’s take a look at a passage now and see what it looks like between first and second draft.

After a day or two, I went back through the passage and did some tweaking. Here’s what it looks like after the polish draft.

You can compare the two and see how I went over the diction and conciseness of voice to tighten or add details as needed to make it richer and clearer, but also improve the pace at the same time. My goal was to write in a voice that implies a certain Midwest country accent without using any dialect or other tricks. I wanted the voice itself to just slip the accent into reader’s minds, but I also want it to be humorous, while still being realistic, gritty while still being believable. This is an example of how you might revise a passage.

Words On The Page

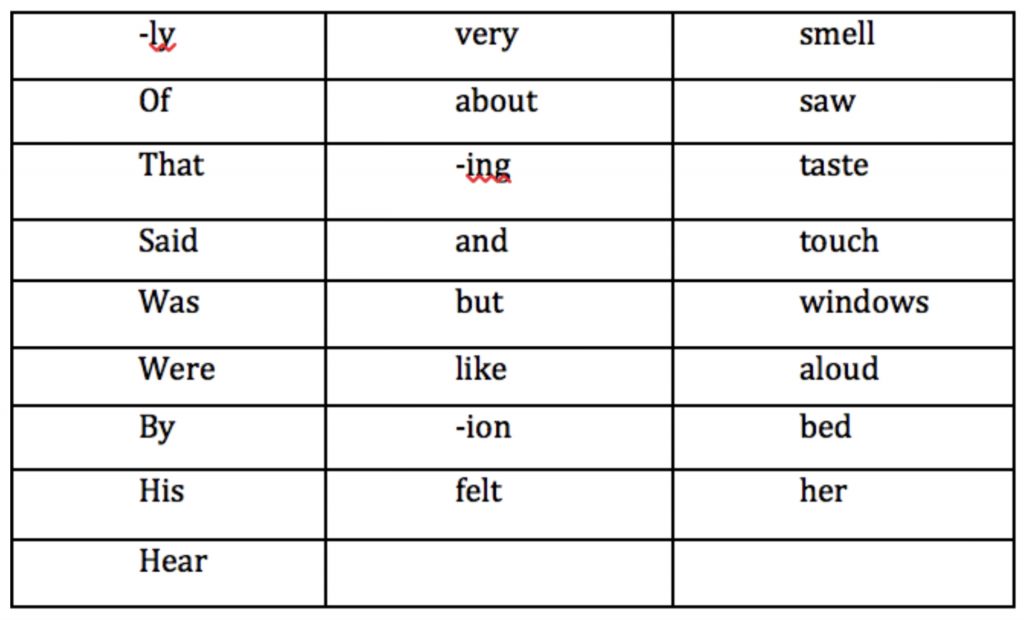

There a few concerns good writers learn to concern themselves with that beginners often leave to their editors or copyeditors. These are things that concern the way words look on the page. Ken Rand writes: “The very shape of letters has a lot to do with whether a reader enjoys or even comprehends the words.” This why choosing fonts is so very important, but additionally, if you have a paragraph with sentences using similar words that appear near each other (in the line above atop or the line below right under) each other, this can confuse readers or cause them to get lost as well. You’ll also want to look for “widows”—solitary words at the end of paragraphs that hang over solo onto the next line. Typesetters and editors will remove these. Your best bet to be sure it’s done the way you want is to find them yourself and see if adding or rearranging words in a sentence can help eliminate them before they ever get there.

I also mentioned earlier in the book that pace and flow of the reading experience come from how pages appear. Too many long descriptive passages with no blank space to breath can make reading difficult and make a book seem slow. Editors and Typesetters may want to break these up just for that purpose. It is in your best interest to make breaks yourself to avoid that, so you wind up with the book exactly as you intended. Looking for this will also aid your search for exposition info dumps and overly long description which you might take out parts of to insert at less busy spots later or just save for another book. Flip through a bound book and notice how the varied flow of pages is pleasing to the eyes as you scan or read, and you’ll get the idea of the subconsciously psychology involved here. It takes time to learn this well, but it is a very worthwhile skill for any author to learn, and allows you to influence parts of the process that tend to move on without you if you don’t know about them. After all, it is your book. You are the one who has to live with it. Wasted time and frustration arguing about recombining paragraphs and other details during editing is something that benefits no one, so the more work you do before then, the better your experience will be.

Knowing When to Stop

Everything we’ve covered so far in this chapter is aimed at one goal: helping you make your manuscript stronger and more professionally polished before passing it on to your editor and publisher. The last tip I want to offer is the answer to a commonly asked question: How do I know when to stop editing?

The best way to know is when you start noticing yourself putting back things you already removed, it’s time to consider stopping and handing it over to someone else. Don’t get stuck in the cycle of endless revision so that you never finish. At some point, you can only make each book as good as you are as a writer at that particular moment. Over time, each book will get better and better, but you do need to learn your limits. And no book will ever be perfect. I usually finish revisions and set the book aside for a day or two before doing another read through aloud. That gives me a break long enough to rest my eyes and brain and come back ready to hear it fresh again and make any final notes as I go through.

When I’ve reached a point that I know it is the best I can make it, then I send it to my agent or editor for the next stage: the editorial process.

For more tips, come back next Wednesday. For previous WriteTips, click here.

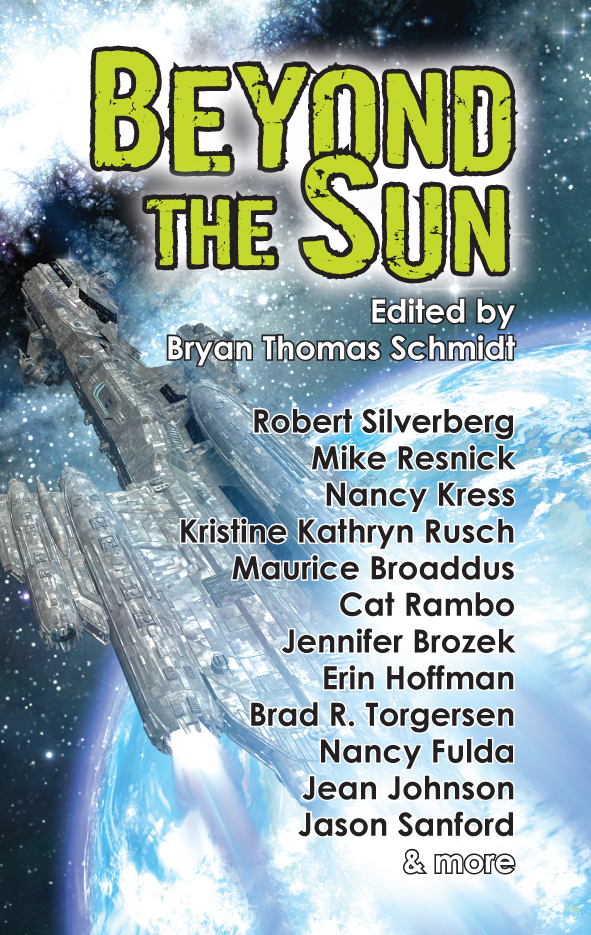

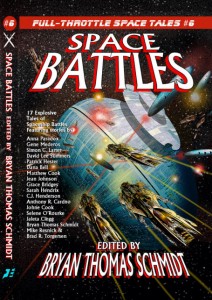

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is a national bestselling author/editor and Hugo-nominee who’s edited over a dozen anthologies and hundreds of novels, including the international phenomenon The Martian by Andy Weir and books by Alan Dean Foster, Frank Herbert, Mike Resnick, Angie Fox, and Tracy Hickman as well as official entries in The X-Files, Predator, Joe Ledger, Monster Hunter International, and Decipher’s Wars. His debut novel, The Worker Prince, earned honorable mention on Barnes and Noble’s Year’s Best Science Fiction. His adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction books have been published by publishers such as St. Martins Press, Baen Books, Titan Books, IDW, and more. Find him online at his website bryanthomasschmidt.net or Twitter and Facebook as BryanThomasS.

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is a national bestselling author/editor and Hugo-nominee who’s edited over a dozen anthologies and hundreds of novels, including the international phenomenon The Martian by Andy Weir and books by Alan Dean Foster, Frank Herbert, Mike Resnick, Angie Fox, and Tracy Hickman as well as official entries in The X-Files, Predator, Joe Ledger, Monster Hunter International, and Decipher’s Wars. His debut novel, The Worker Prince, earned honorable mention on Barnes and Noble’s Year’s Best Science Fiction. His adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction books have been published by publishers such as St. Martins Press, Baen Books, Titan Books, IDW, and more. Find him online at his website bryanthomasschmidt.net or Twitter and Facebook as BryanThomasS.

To download How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction free one book, click here.

To check out Bryan’s latest novels, click here.