The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 8:

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 8:

Last week, I wrote about The Key To Good Plotting—Asking The Right QuestionsThe Key To Good Plotting—Asking The Right Questions, this week I want to talk about more ways to build suspense in your storytelling, specifically through creating tension using dialogue and emotions. This post is longer because of numerous examples, so please stick with it.

“Holding readers’ attention every word of the way,” writes Donald Maass in The Breakout Novelist, “is a function not of the type of novel you’re writing, a good premise, tight writing, quick pace, showing not telling, or any of the other widely understood and frequently taught principles of storytelling. Keeping readers in your grip comes from something else…the moment-by-moment tension that keeps readers in a constant state of suspense over what will happen—not in the story, but in the next few seconds.” This kind of microtension comes not from story but from emotions, specifically conflicting emotions. So above all else, creating suspense is about making readers care.

“Holding readers’ attention every word of the way,” writes Donald Maass in The Breakout Novelist, “is a function not of the type of novel you’re writing, a good premise, tight writing, quick pace, showing not telling, or any of the other widely understood and frequently taught principles of storytelling. Keeping readers in your grip comes from something else…the moment-by-moment tension that keeps readers in a constant state of suspense over what will happen—not in the story, but in the next few seconds.” This kind of microtension comes not from story but from emotions, specifically conflicting emotions. So above all else, creating suspense is about making readers care.

Webster’s Dictionary defines suspense as: a. The state of being undecided or undetermined; 2. The state of being uncertain, as in awaiting a decision, usually characterized by some anxiety or apprehension.

What is undecided and undetermined are story questions. First and foremost, suspense is about questions. James N. Frey writes in How To Write a Damn Good Novel II: “A story question is a device to make the reader curious. Story questions are usually not put in question form. They are rather statements that require further explanation, problems that require resolution, forecasts of crisis, and the like.”

An hour before sunset, on the evening of a day in the beginning of October, 1815, a man traveling afoot entered the little town of D------. The few persons who were at this time at their windows and doors, regarded this traveler with a sort of distrust.

Thus opens Book 2 of Victor Hugo’s classic masterpiece Les Miserables. The story questions are “who is this man?” and “is he dangerous?” The first question intrigues, the second raises the suspense, and this is how story questions work. Other examples:

The great fish moved silently through the night water, propelled by great sweeps of its crescent tail.

(Jaws, Peter Benchley: “Who will be the shark’s lunch?”)

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

(Pride and Pejudice, Jane Austen: “Who’s the single man?” And “Who’s going to be the lucky girl?”)

Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charms as the Tarleton twins were.

(Gone With The Wind, Margaret Mitchell: “What are the consequences of the twins being charmed? Will they fight over her?“ Etc.)

Expanding on last week’s post, Frey goes on to say: “Story questions, unless they are powerful, life-and-death questions that are strengthened, reinforced, and elaborated will not hold the reader long.” When they occur at the beginning of a story, they act as “hooks” that draw readers in. That’s why so many classic novels start with hooks and yours should, too. Ultimately, raising story questions—unanswered questions, characters we care about, and tension are the keys to suspense in any story.

Creating Tension

Since we just discussed it, let’s start with dialogue. Dialogue in novels is not realistic. Every word is thought through and constructed to create the upmost tension and steadiest pace. Characters say what they mean, are rarely interrupted, don’t stumble over words, and all the same the words often seem unimportant if taken by themselves. The words are not what holds the power. The power comes from the meaning, the motivations of the speakers, and the underlying conflict. Here’s an example from John Sandford’s Rule Of Prey:

“Daniel’s hunting for you.” Anderson looked harassed, teasing his thinning blonde hair as he stepped through Lucas’ office door. Lucas had just arrived and stood rattling his keys in his fist. “Something break?” “We might go for a warrant.” “On Smithe?” “Yeah. Sloan spent the night going through his garbage. Found some wrappers from rubbers that use the same kind of lubricant they found in the women. And they found a bunch of invitations to art shows. The betting is, he knows the Ruiz chick.” “I’ll talk to the chief.”

Now, tension in this scene comes from two things. One, starting abruptly with dialogue that is a warning or feels urgent in a way before establishing setting and that Detective Lucas Davenport, our protagonist, has just arrived. Two, the underlying tension of the hunt for the killer and the chief wanting Lucas. The words themselves are fairly innocuous at face value, a bunch of information really. In another context, they might play very differently, but here they carry urgency, a sense of danger, emotional foreboding. A sex killer is loose and the cops are racing to find him. Yes, some of this was established in earlier scenes, but just from this little short scene alone, you get a lot of it. This dialogue drips with tension as a result. What makes dialogue gripping is not the information or facts imparted, but the tension, the urgency. The tension comes from the people, not the words.

Let’s look at another example from Every Dead Thing by John Connelly:

“Nice story, Tommy,” said Angel.

“It’s just a story, Angel. I didn’t mean nothing by it. No offense intended.”

“None taken,” said Angel. “At least not by me.”

Behind him there was a movement in the darkness, and Louis appeared. His bald head gleamed in the dim light, his muscular neck emerging from a black silk shirt within an immaculately cut gray suit. He towered over Angel by more than a foot, and as he did so, he eyed Tommy Q intently for a moment.

“Fruit,” he said. “That’s a…quaint term, Mr. Q. To what does it refer, exactly?”

The blood had drained from Tommy Q’s face and it seemed to take a long time for him to find enough

saliva to enable him to gulp. When he did eventually

manage, it sounded like he was swallowing a golf ball.He opened his mouth but nothing came out, so he closedit again and looked at the floor in vain hope that it

would open up and swallow him.

“It’s okay, Mr. Q, it was a good story,” said Louis ina voice as silky as his shirt.

“Just be careful how you tell it.” Then he smiled a

bright smile at Tommy Q, the sort of smile a cat mightgive a mouse to take to the grave with it. A drop of sweat ran down Tommy Q’s nose, hung from the tip a moment, then exploded on the floor.

By then, Louis had gone.

The tension here comes from the characters, not the dialogue. Separate the dialogue out and there’s nothing particularly tense about it, but the context is that Tommy Q has just laughingly told Angel a story about a gay man’s murder. Louis and Angel are gay and they are killers, particularly Louis. Puts a whole new spin on it, doesn’t it? That’s how tension in dialogue works. I imagine that even not knowing everything beforehand, you felt the tension reading it, but now that I’ve told you, read it again. Even more tense, right? We keep reading at moments like this not because of what they say. We keep reading to see if they will reconcile or fight. Will the tension explode into a fight or resolve?

Ask yourself where the tension is in your dialogue? Look at every passage, every word. How can it be improved? Does the tension come from the words or the situations, the circumstances and characters? Make sure the emotional friction between the speakers is the driving force.

Tension in action works much the same way. Yes, there can be violence and that has an inherent tension. But even in scenes with action that is nonviolent, you need tension. Let’s look at a scene from Harlan Coban’s Tell No One:

I put my hands behind my head and lay back. A cloud passed in front of the moon, turning the blue night into something pallid and gray. The air was still. I could hear Elizabeth getting out of the water and stepping onto the dock. My eyes tried to adjust. I could barely make out her naked silhouette. She was, quite simply, breathtaking. I watched her bend at the waist and wring the water out of her hair. Then she arched her spine and threw back her head. My raft drifted farther away from shore. I tried to sift through what had happened to me, but even I didn’t understand it all. The raft kept moving. I started losing sight of Elizabeth. As she faded in the dark, I made a decision: I would tell her. I would tell her everything. I nodded to myself and closed my eyes. There was a lightness in my chest now. I listened to the water gently lap against my raft. Then I heard a car door open. I sat up. “Elizabeth?” Pure silence, except for my ownbreathing. I looked for her silhouette again. It was hard to make out, but for a moment I saw it. Or thought I saw it. I’m not sure anymore or if it even matters. Either way, Elizabeth was standing perfectly still, and maybe she was facing me. I might have blinked—I’m really not sure about that either—and when I looked again, Elizabeth was gone.

Lots of description, and fairly benign at that. Only one line of dialogue. But what lends tension to this is the descriptive details that follow what is obviously an important decision by the narrator to confess something to Elizabeth. Is she gone? Did someone else arrive? Who? That the narrator, David, is deeply in love and feels guilt over a secret is obvious. It doesn’t need to be stated. And that underscores the tension of otherwise mundane action. We want to see what happens. This is how action, even nonviolent, can drip with tension if written well, and it needs to if your book is to hook readers time and again and keep them reading.

Exposition always risks boring readers. Maass writes: “Many novelists merely write out whatever it is that their characters are thinking or feeling—or, more to the point, whatever happens to occur to the author in a given writing session. That is a mistake.” Most commonly, exposition fails because it merely restates what we have already learned from the story or information characters would already know. It becomes uninteresting or false because it feels unnecessary. The key to good exposition is to frame it so it offers new ideas and emotions into the tapestry of the story. Remember when I said you should only give us what we need to know to understand the story at any given moment? That’s why choosing placement of your exposition carefully is so important. Save it until we need it so it brings something useful and important to the story. Don’t just dump it all at once to be stored up for later use. Instead, leave it until it will advance the story.

In Pretties, Scott Westerfeld manages to offer exposition that creates conflicting feelings in the character at the same time.

As the message ended, Tally felt the bed spin a little. She closed her eyes and let out a long, slow sigh of relief. Finally, she was full-fledged Crim. Everything

she’d ever wanted had come to her at last. She was beautiful, and she lived in New Pretty Town with Peris

and Shay and tons of new friends. All the disasters and terrors of the last year—running away to Smoke, living there in pre-Rusty squalor, traveling back to

the city through the wilds—somehow all if it had worked out.

It was so wonderful, and Tally was so exhausted, that belief took a while to settle over her. She replayed Peris’s message a few times, then pulled off the smelly, smokey sweater with shaking hands and threw it

in a corner. Tomorrow, she would make the hole in the wall recycle it.

Tally lay back and stared at the ceiling for a while. A ping from Shay came, but she ignored it, setting her

interface ring to sleeptime. With everything so

perfect, reality seemed somehow fragile, as if the

slightest interruption could imperil her pretty future. The bed beneath her, Komachi Mansion, and even the. city around her—all of it felt as tenuous as a soap

bubble, shivering and empty.

It was probably just the knock on her head causing the

weird missingness that underlay her joy. She only needed a good night’s sleep—and hopefully no hangover tomorrow—and everything would feel solid again, as perfect as it really was.

Tally fell asleep a few minutes later, happy to be a Crim at last.

But her dreams were totally bogus.

So on the surface, she is happy to have accomplished her goal and become a Crim. But she has to try hard to convince herself of it. Too hard. That life is perfect. So hard that it is obvious she is not convinced it is real, that she fears it may be bogus. This underlying emotional conflict makes the exposition feel important and relevant in a way the words never would have. It advances the story and adds tension, keeping our interest.

The trick to making exposition matter is to dig deeper into your characters at such moments and examine what is going on with them. Why is this information important at this moment? What do they feel in saying it and why does it matter? Find the delimmas, contradictions, impulses, and conflicting ideas and questions that drive the character and readers will be fascinated. Maass writes: “True tension in exposition comes not from circular worry or repetitive turmoil; it comes from emotions in conflict and ideas at war.”

Description passages have a similar problem, which is why readers sometimes skim them. Maass writes: “Description itself does nothing to create tension; tension only comes from people within the landscape.” So the trick is to use description to reveal the conflict of the observer. How does observing various details affect the character? What makes the details stand out for the character? People tend to focus on details that mean something to them and ignore the rest. So pick the details that are important to the character and describe them so it’s clear why they count. Here’s a great example from Memory Man by David Baldacci:

The bar was much like every bar Decker had ever been in.

Dark, cold, musty, smoky, where light fell funny and everyone looked like someone you knew or wanted to know. Or, more likely, wanted to forget. Where everyone was your friend until he was your enemy and cracked a pool stick over your skull. Where things were quiet until they weren’t. Where you could drink away anything life threw at you. Where a thousand Billy Joel wannabes would serenade you into the wee hours.

Sounds like most bars I’ve been in for sure. There are elements of familiarity and elements of foreboding. Decker is both at home and ill at ease here, conflicting emotions. The history in the elements described keeps him on edge and we with him. And as a result, we feel the tension of anticipation that something will happen here. And in fact, it does. A confrontation follows moments later.

Maass writes: “Tension can be made out of nothing at all—or, at least, that’s how it can appear. In reality, it is feelings—specifically, feelings in conflict with each other—that fill up an otherwise dead span of story and bring it to life.” Finding ways to bring out those conflicting emotions through description is the key to keeping tension in every word.

Some of you know I’ve been working on a new project with friends called Boralis Books. Boralis Books arose out of my frustration with New York publishing rejecting strong, well written page turners because they “didn’t know how to market them.” It’s happened to me several times and I know other authors have experienced the same frustration. So I decided to publish some novels myself, and to me, the best way to do it is to create a press and recruit staff—editors, proofers, designers—and try and put out quality product that rivals New York quality books.

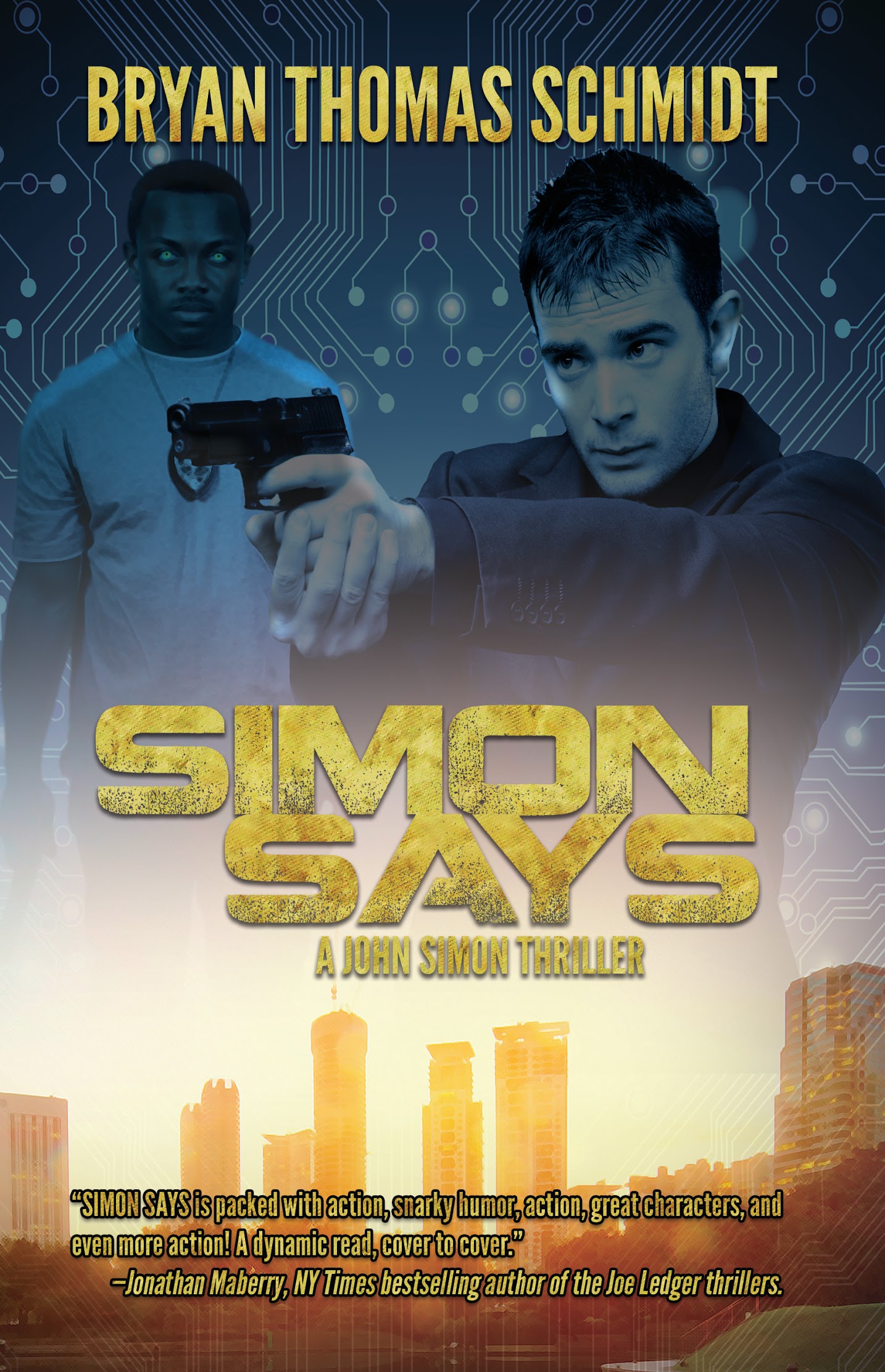

Some of you know I’ve been working on a new project with friends called Boralis Books. Boralis Books arose out of my frustration with New York publishing rejecting strong, well written page turners because they “didn’t know how to market them.” It’s happened to me several times and I know other authors have experienced the same frustration. So I decided to publish some novels myself, and to me, the best way to do it is to create a press and recruit staff—editors, proofers, designers—and try and put out quality product that rivals New York quality books. Meanwhile, we plan to publish both speculative fiction and mystery/thriller with a few others possibly mixed in. We hope you’ll check out what we’re doing. Our first release will be Simon Says, the firs in my John Simon thrillers, which is Bosch meets Lethal Weapon with robots. It’s filled with action, strong memorable characters and humor and set in 2029 Kansas City, with a tough Luddite cop teaming with an android witness to solve a nanotech crime and his partner’s kidnapping. Future books will follow.

Meanwhile, we plan to publish both speculative fiction and mystery/thriller with a few others possibly mixed in. We hope you’ll check out what we’re doing. Our first release will be Simon Says, the firs in my John Simon thrillers, which is Bosch meets Lethal Weapon with robots. It’s filled with action, strong memorable characters and humor and set in 2029 Kansas City, with a tough Luddite cop teaming with an android witness to solve a nanotech crime and his partner’s kidnapping. Future books will follow. Diction and Dialect

Diction and Dialect ["I function ninety percent like a human being in most respects," Lucas said as they continued up the stairs.

"Yeah, and at least ten percent is how you talk," Simon teased.

Lucas turned a puzzled look at him. "You think I do not speak like a human?"

"No normal human uses the cadence you use, no," Simon said.

Lucas looked disappointed. "Well, I hope you will assist me to do better. I am designed to blend in with humans and wish to learn."

"You want to blend stop saying things like 'in most respects' or 'I am designed,'" Simon said, shaking his head. "You sound like a machine."

Lucas hrmphed. "I will remember."

["I function ninety percent like a human being in most respects," Lucas said as they continued up the stairs.

"Yeah, and at least ten percent is how you talk," Simon teased.

Lucas turned a puzzled look at him. "You think I do not speak like a human?"

"No normal human uses the cadence you use, no," Simon said.

Lucas looked disappointed. "Well, I hope you will assist me to do better. I am designed to blend in with humans and wish to learn."

"You want to blend stop saying things like 'in most respects' or 'I am designed,'" Simon said, shaking his head. "You sound like a machine."

Lucas hrmphed. "I will remember."  Here’s an example from my novel The Worker Prince:

Here’s an example from my novel The Worker Prince: Remember that characters may speak differently to one character than another depending upon their relationship, their motives, etc. If hanging with old friends from the old ghetto, one may slip into a dialect left behind in childhood for those interactions even if the character usually speaks in a more refined way with characters outside that world and life. Ever have a friend from a foreign country or the U.S. Deep South who talks with one accent with you but goes home and slips back into a native accent? People speak to a lover different than a mother or a sister or a boss or a priest. One also speaks differently to a king or ruler than a fellow citizen and often to a teacher than fellow students, and so on. So remember to establish changes in dialogue appropriate to the circumstances in which the dialogue is occurring and who and to whom the characters are speaking. This will make your world come alive and feel realistic.

Remember that characters may speak differently to one character than another depending upon their relationship, their motives, etc. If hanging with old friends from the old ghetto, one may slip into a dialect left behind in childhood for those interactions even if the character usually speaks in a more refined way with characters outside that world and life. Ever have a friend from a foreign country or the U.S. Deep South who talks with one accent with you but goes home and slips back into a native accent? People speak to a lover different than a mother or a sister or a boss or a priest. One also speaks differently to a king or ruler than a fellow citizen and often to a teacher than fellow students, and so on. So remember to establish changes in dialogue appropriate to the circumstances in which the dialogue is occurring and who and to whom the characters are speaking. This will make your world come alive and feel realistic.

One of our most cherished values, codified in our U.S. Constitution under the Bill of Rights, is freedom of speech. It’s covered in the First Amendment, under the same clause that establishes Freedom of Religion, and reads as follows:

One of our most cherished values, codified in our U.S. Constitution under the Bill of Rights, is freedom of speech. It’s covered in the First Amendment, under the same clause that establishes Freedom of Religion, and reads as follows: