The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 5:

What Is Voice?

Voice is a combination of the character viewpoints and your own. While it is important to avoid jarring readers out of the story by intruding too much as the narrator, inevitably your own unique way of saying things will always come through. And it should. In Writing the Breakout Novel, Donald Maass explains that when editors talk of voice, “they mean not only a unique way of putting words together, but a unique sensibility, a distinctive way of looking at the world, an outlook that enriches an author’s oeuvre. They want to read an author who is like no other.” Voice is your unique writing language and approach, reflecting your own diction and style along with that of the characters. Maass adds: “You can facilitate voice by giving yourself the freedom to say things in your own unique style… To set your voice free, set your words free. Set your characters free. Most important, set your heart free.” Voice is indeed the single most unique thing any writer brings to their storytelling.

Voice is a combination of the character viewpoints and your own. While it is important to avoid jarring readers out of the story by intruding too much as the narrator, inevitably your own unique way of saying things will always come through. And it should. In Writing the Breakout Novel, Donald Maass explains that when editors talk of voice, “they mean not only a unique way of putting words together, but a unique sensibility, a distinctive way of looking at the world, an outlook that enriches an author’s oeuvre. They want to read an author who is like no other.” Voice is your unique writing language and approach, reflecting your own diction and style along with that of the characters. Maass adds: “You can facilitate voice by giving yourself the freedom to say things in your own unique style… To set your voice free, set your words free. Set your characters free. Most important, set your heart free.” Voice is indeed the single most unique thing any writer brings to their storytelling. The best way to develop your voice is to read thoughtfully a lot. Pay attention to and study what other writers are doing that you like and don’t like, then imitate it. Practice writing in their various voices, and play around to develop your own. What stands out about a particular voice? What types of details do they tend to use most often, and how do they affect you as a reader? What do they say about the world and characters? If you want to be a good writer, you must read. All too many writers make the excuse that they don’t have time to read. I read a book or two a week and still hit 1,300 words a day on average when on a book project. If you make it a priority, it will happen, and consider it part of your work research and author development time. It really is that valuable. Not only can you stay abreast of the latest trends and shifts in genres and subgenres, but you will discover much about what works and doesn’t in fiction that will be invaluable to you in developing your own craft—especially voice and style.

The best way to develop your voice is to read thoughtfully a lot. Pay attention to and study what other writers are doing that you like and don’t like, then imitate it. Practice writing in their various voices, and play around to develop your own. What stands out about a particular voice? What types of details do they tend to use most often, and how do they affect you as a reader? What do they say about the world and characters? If you want to be a good writer, you must read. All too many writers make the excuse that they don’t have time to read. I read a book or two a week and still hit 1,300 words a day on average when on a book project. If you make it a priority, it will happen, and consider it part of your work research and author development time. It really is that valuable. Not only can you stay abreast of the latest trends and shifts in genres and subgenres, but you will discover much about what works and doesn’t in fiction that will be invaluable to you in developing your own craft—especially voice and style.

Let’s look at examples from two classic books which I borrow from Frey’s How to Write a Damn Good Novel II. First, from Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell:

Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charm as the Tarleton twins were. In her face were too sharply blended the delicate features of her mother, a Coast aristocrat of French descent, and the heavy ones of her florid Irish father. But it was an arresting face, pointed of chin, square of jaw. Her eyes were pale green without a touch of hazel, starred with bristly black lashes and slightly tilted at the ends. Above them, her thick black brows slanted upward, cutting a startling oblique line in her magnolia white skin—the skin so prized by Southern women and so carefully guarded with bonnets, veils, and mittens against hot Georgia suns.

Okay, let’s examine what all we learn here. First, we learn what Scarlet looks like in many details and that she is not considered beautiful but is charming. We learn of her French and Irish parentage as well. Additionally, we learn of the Southern attitudes toward pale skin and beauty. So there is appearance, heritage, and cultural context all in a few sentences of very specific details. These are the kinds of details that give the voice authority, and while the voice is neutral and not passing judgments, its melodramatic tone does aid the tone of the larger story.

Next, here’s a passage from Stephen King’s Carrie:

Momma was a very big woman, and she always wore a hat. Lately her legs had begun to swell and her feet always seemed on the point of overflowing her shoes. She wore a black cloth coat with a black fur collar. Her eyes were blue and magnified behind rimless bifocals. She always carried a large black satchel purse and in it was her change purse, her billfold (both black), a large King James Bible (also black) with her name stamped on the front in gold, a stack of tracts secured with a rubber band. The tracts were usually orange, and smearily printed.

Note the feel of sarcastic or ironic tone to this narrative voice. There are rich details, but the tone lends almost a sense of commentary to the descriptions. “Her feet always seemed on the point of overflowing her shoes” is a very specific detail that evokes an immediate image of fat feet crammed into too-small shoes, and the clothing and accessories are big and stand out to match the big woman and make her stand out, intentional or not. We also see she is a Christian or at least a Bible reader, and the public display of this, along with her size, makes her come across as foreboding, even perhaps a bit serious or intimidating. These kinds of subtle details are vivid and memorable and create characters who readily reflect the complex people we meet in the world around us, making the author’s voice ring with truth that inspires confidence in its telling of the story.

In his stunning debut Harry Bosch novel, The Black Echo, Michael Connelly introduces his main narrative voice and protagonist with a flashback dream that tells us volumes about the character without stating it outright:

Harry Bosch could hear the helicopter up there, somewhere above the darkness, circling up in the light. Why didn’t it land? Why didn’t it bring help? Harry was moving through a smoky, dark tunnel and his batteries were dying. The beam of the flashlight grew weaker every yard he covered. He needed help. He needed to move faster. He needed to reach the end of the tunnel before the light was gone and he was alone in the black. He heard the chopper make one more pass. Why didn’t it land? Where was the help he needed? When the drone of the blades fluttered away again, he felt the terror build and he moved faster, crawling on scraped and bloody knees, one hand holding the dim light up, the other pawing to keep his balance. He did not look back, for he knew the enemy was behind him in the black mist. Unseen, but there, and closing in.

When the phone rang in the kitchen, Bosch immediately woke…

Note the mixture of narrative description with inner thoughts that provide emotional context for what the character is experiencing. When he thinks, “Why didn’t it land? Why didn’t it bring help?” we suddenly know he is feeling afraid or in trouble, when all we have been told before this is that he heard the helicopter. This sets the emotional tone and tension for what follows. The “smoky, dark tunnel” as setting lends an air of danger to it that just adds to the tension, and his dying flashlight, which the comment on batteries tells us before the word “flashlight” is even introduced, also ups the stakes. Who hasn’t been afraid in the misty dark with a dying flashlight? No mention is made of fear or terror until the helicopter has appeared for the third time and he is then crawling, his knees in pain, desperate to escape the dark. This shows how the right details, ordered carefully, can create a whole atmosphere, tone, and ambience that indicates so much more than actually needs to be said, demonstrating how a character’s own experiences and background affect and interplay with what he or she is experiencing in the immediate moment of the story scene.

If this isn’t how you read, then you should start, because this is how one reads and studies the craft. It will transform your reading into work at times, for sure, but if you don’t pay attention to such details, a good book will catch you up and breeze you away without helping you notice the stylistic choices that make up the voice so you can think about them as you develop your own voice or voices. I say “voices” because most writers have more than one and employ them as needed in different genres and books or stories that they write. Few writers have only one voice, but again, it takes time to develop the voices and write in them with confidence, because none of your narrative voices will ever be completely you at any point as you naturally converse or think in the world. All of them are amalgamations of character and author, affected by considerations of diction, tone, and more. Your fiction will always take on a personality of its own, and it should do so well. That personality is not you nor is it just a character, but a combination of them.

One thing narrators can do that characters and authors cannot is legitimize character and world by showing the characters’ emotional reactions to various circumstances and actions they experience. The narrative voice can speak as if it knows them intimately and cares deeply about them or loathes them, depending upon the needs of the situation. It can legitimize their pain and anger or characterize it as unusual or inappropriate in ways that will guide the reader’s own opinions and impressions and guide them along in how they connect with the story. In Voice and Style, Johnny Payne writes: “The narrating voice provides a more sensible and level-headed account than the character’s simply because its passions are not engaged in the flow of the action in the same way.” Unlike the character, the narrator doesn’t have anything to lose or gain. They don’t have to worry about the reactions of other characters or consequences for its thoughts or actions. They can merely observe, comment, and hover like a ghost. Of the difference between first- and third-person narration, Payne reminds us: “Third-person narrators tend to offer more range and elicit fewer questions, while first-person narrators, even when they’re volatile, offer the advantage of a more immediate and tangible voice.” This is because the first-person “I was” lends itself to a feel of being closer to events and actions in the story than the third-person “he was.” The first is talking about itself and the third about some stranger, removed from the self.

The voice is key to setting atmosphere and tone by its word choices. It can layer a mood over any scene just by how it describes the events and characters as the scene unfolds. The wellspring here is character emotions grounded objectively in the setting. Authors should not engage in atmospherics or hysterics. That kind of melodrama should instead flow from the characters themselves. Description should never be written for its own sake but should serve the characters and story always, every time. This is how the writer guides the storytelling without inserting himself or herself directly into it. Tone always flows from who is telling the story, whereas point of view flows from character. The author brings the tone, the character brings the point of view, and the two combine and unify into one narrative voice that sets forth the story dramatically, weaving the emotional tone, atmosphere, etc. necessary to engage readers and tell the story with the appropriate gravitas and effect. The impression your story makes, Payne reminds us, “will depend to a large degree on the tone established at the beginning and sustained throughout the performance.” This is why sometimes reviews note changes in tone that render novels less effective or troubled. Consistency in tone is very important to readers and their experience of receiving a story.

Ultimately, if you set the proper tone and maintain it, providing the right details to gain confidence from your reader, your main responsibility as a writer is then to ensure you honor the author–reader contract, making all the details and emotions of the story pay off rewardingly for readers.

My Google search just found this awesome deep discount on the PREDATOR: IF IT BLEEDS Audiobook, for those who might be interested.

My Google search just found this awesome deep discount on the PREDATOR: IF IT BLEEDS Audiobook, for those who might be interested.

NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful.

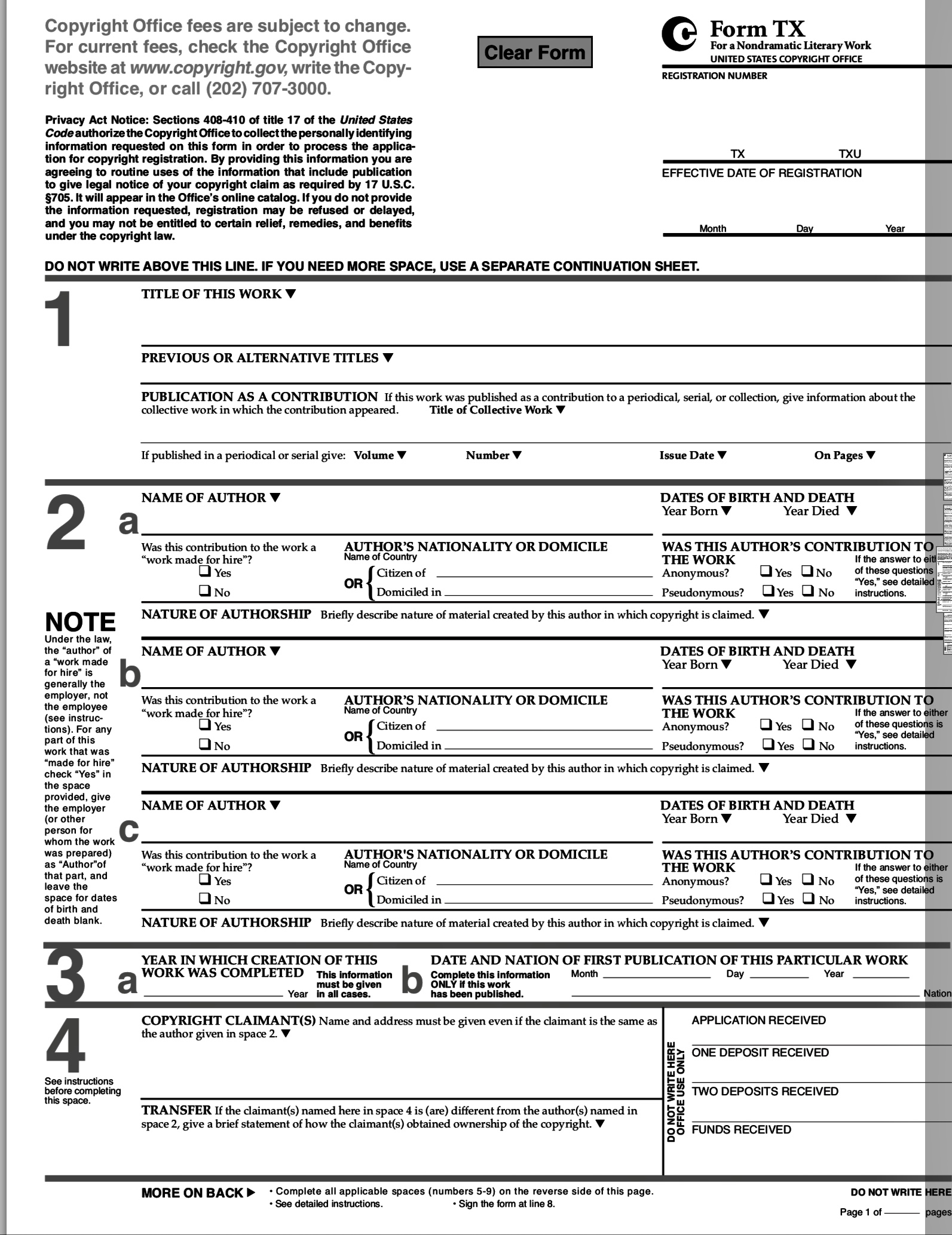

NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful. 1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.

1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.