The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 2:

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 2:

Readers want your characters to seem like real people, whole, alive, believable, and worth caring about. People become, in our minds, what we see them do, so first thing first, your character is what he or she does.

But just seeing what someone does isn’t enough in good storytelling. To truly know a person, we need to understand their inner self, their motives. Motive is what gives moral value to their actions. And what a character does, no matter how good or bad, is never morally absolute. A character is what he or she means to do, but we all make mistakes, we all have flaws. So, the intention they have and the ideal they desire to be and will become by the end of your story is even more important. Even if their motive is concealed from readers for much of the book, as often is the case with the antagonist, and even if they themselves are not always certain what is driving them due to some psychological trauma or issue, you need to know their motive clearly as you write, and they need to have one.

Here are some key things you need to know about your characters to write them well:

Here are some key things you need to know about your characters to write them well:

Their Name—This may seem obvious. But every once in a while, you get some person who thinks they are clever and decides to write a mysterious unnamed character. This is very hard to pull off and poses and number of problems, but even if you try it, you still need to know their name. Names tell us lots about a person, from their background and history to ethnicity, culture, age, and more. A name is invaluable to helping know your character and to helping readers know them as well.

Their Past—Our past, however we might revise it in memory, is who we believe we are. It shapes our image of ourselves.

Their Reputation—Characters are also restricted and affected by what others think of and expect of them. How are they known? Who do others think they are?

Their Relationships—Who is important to them? Who do they love? Who do they have relationships with that are good, and who do they have bad relationships with and why? And how does this affect their motives and actions and their self-perception? Not all of these relationships will be used in the story or appear on screen, so to speak, but they are part of who the character is and is becoming and what drives them, so you need to know them.

Their Habits and Patterns—Habits and patterns imply things about a person. From personal tics to emotional patterns, we form our expectations based on these characteristic habits that suggest how they will behave in any given situation; often these traits communicate unspoken things about the character’s state of mind, emotions, and more. Many story possibilities can emerge from these. And they make the character seem more well-rounded and realistic because every real person we know has these aspects if we take time to study them.

Their Talents and Abilities—Talents do not have to be extreme to make them a part of a character’s identity or even important to their fate. But what they do well and don’t do well does matter to us, to them, and to those around them, and also to how they take action and respond to the world around them throughout the story.

Their Tastes and Preferences—Someone can like all the same things you do and still not be someone you want to spend time with or would trust to care for your pets or kids. Tastes and preferences tell us a lot about someone while also opening story possibilities and potential conflicts that can help drive the story and build characters and relationships.

Their Appearance—What color are their eyes? Do they have any handicaps? What color is their hair? These are not characterization alone, but they add depth and they can affect self-esteem and how characters are perceived by readers and by other characters, so they matter.

In filling out a character profile that identifies all these characteristics, observe people you know. Think about people you have seen and encountered. What stands out about them? What annoyed you? What did you love? And can any of these things be used to make a real, interesting, dimensional character?

There are three questions readers will ask that must always be considered. And they expect good answers at some point to hold their interest. In fact, your honeymoon with readers lasts only a few paragraphs, so you must constantly keep such questions in mind.

- Why should I care about what’s going on in the story?

- Why should I believe anyone would do that?

- What’s happening?

Fail to answer these questions at your own peril. It may sound harsh, but do your job and it will almost never be an issue. Uncertainties can be part of storytelling, but even intentional uncertainties must be clear, so readers will know you meant it to be that way and continue to trust you to pay it off later. Trust between reader and author is key to any novel’s success. As always, you need to know a lot more about your characters than readers may need for understanding the present story. Some of this stuff may never get written directly into your book, but knowing it may profoundly impact how you write your character and will be very useful in keeping clearly in mind who they are and how they move through the world and interact with it.

NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful.

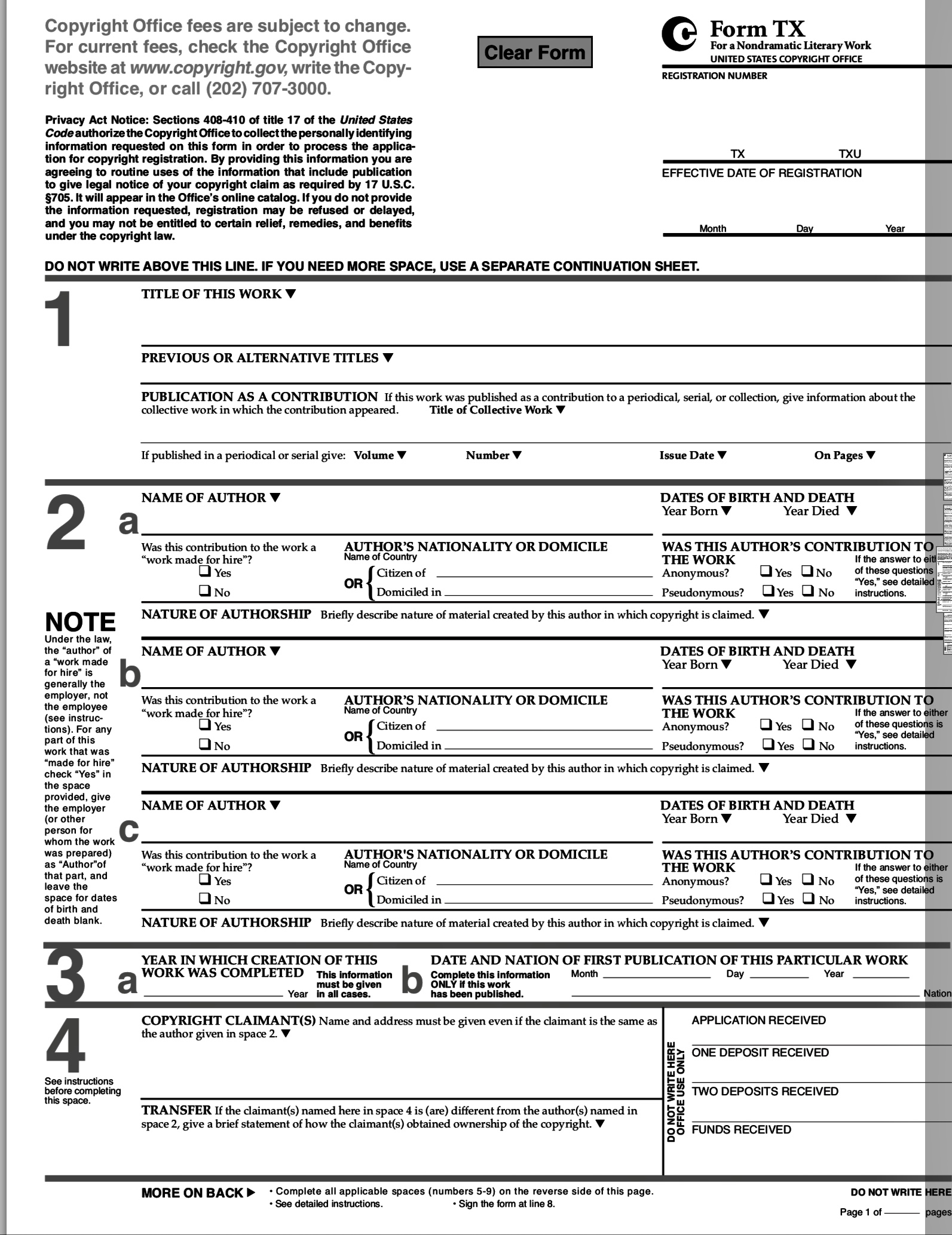

NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful. 1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.

1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.