The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 13: Editing & Rewriting. It is part 2 of a multi-part series. For Part 1, click here.

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 13: Editing & Rewriting. It is part 2 of a multi-part series. For Part 1, click here.

Once you get your mind in the game, it’s time to start the read-through and notetaking. Once you’ve done that, it’s time to dig in, so let’s look at some common problems you should look for in every manuscript.

Self-Editing Tips for Common Problems

What I am about to teach you is merely an overview of tips you can use to polish your manuscripts and make them more professional when you send them on to a professional editor. In no way will this information qualify you to not need an editor nor will it be a guaranteed fix for all the issues in a manuscript. I am an editor and I still need an editor for my writing. So will you. Now the right brain is your creative side. To edit well, you must switch brains and use your left brain. This is why editing should not begin until you’ve given yourself some time away to gain back a little fresh perspective or objectivity. It is also why techniques such as reading backwards, last sentence first, or reading aloud are very helpful tools to editing and revision.

Saving your editor time and impressing them with your professionalism isn’t just about making yourself and your book look good. It’s also about maximizing the value you can get from an editor’s additional input. The cleaner the manuscript, the less they have to worry about silly basics and the more they can concentrate on the larger, more complex nuances of your writing. And that will allow them to focus on what really makes the difference between a truly great book and a mediocre one.

The 10% Solution Method

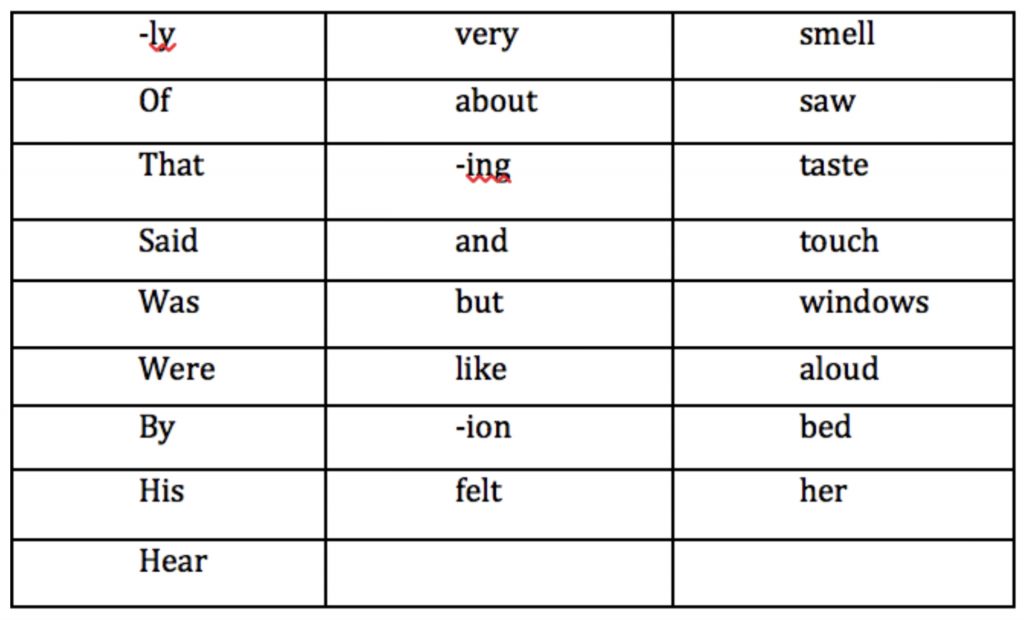

The first technique is from Ken Rand’s The 10% Solution. The basic premise is this: by taking your word count and reducing it by 10 percent, you can and will eliminate a lot of fat to tighten up and add sparkle and confidence to your manuscript. As you develop as a writer, you will come up with lists to check in editing of your most overused words, most misspelled words, etc. These are often key areas for eliminating 10 percent, but here are some others. Use the following table:

Take these words and insert them one by one on your find-replace feature of your word-processing program and highlight the results. Then go through and look at them one by one, asking yourself three questions:

1. Do I keep it as is?

2. Do I change it?

3. Do I delete it?

Then ask yourself if the sentence is accurate, clear, and brief before and after. If it is accurate, clear, and brief before, you likely will choose one and keep it as is. If not, changes are warranted.

For “-ion,” it is the last three syllables of many long words. Here you may just need to consider substitutes. Instead of “intoxication,” does “drunk” work better? For “conflagration,” what about “fire”? For “rationalization,” how about “excuse”? Remember, writing is about communication. The simpler, the clearer it is. If it is the vocabulary of a character, that is one thing. Some characters have different social and educational levels and styles and that should be represented, of course, but in general use of language, the simpler, clearer choice is usually better.

For “-ion,” it is the last three syllables of many long words. Here you may just need to consider substitutes. Instead of “intoxication,” does “drunk” work better? For “conflagration,” what about “fire”? For “rationalization,” how about “excuse”? Remember, writing is about communication. The simpler, the clearer it is. If it is the vocabulary of a character, that is one thing. Some characters have different social and educational levels and styles and that should be represented, of course, but in general use of language, the simpler, clearer choice is usually better.

Repeat this until you’ve gone through the entire list. These are generally the most overused and abused words by authors, and there are reasons for them, from passives like “was” and “were” and “felt” to repetitive words like “said,” “that,” and “but” to weak intruders like “saw,” and more. Applying this technique will help you identify many weaker sentences you need to polish and words you need to eliminate to make your prose stronger.

Intruder Words

The next tip is to find and identify intruder words in your manuscript. Intruder words lend a feel of passive writing or structure to the narrative. Use them only when consciously aware of doing so, not as a fallback or style. The more active way to state things is to just flat out state it. Ken Rand writes in The 10% Solution, “When you show the world filtered through a character’s senses, you distance your reader one degree from sensing the story environment themselves.” It’s like reading through an interpreter, which takes you out of immersion to a step removed. The most common intruder words are “knew,” “know,” “felt,” “wondered,” “thought,” “mused,” “debated,” and “saw.”

Example 1: He wondered what kind of food she was cooking as he pushed on the front door and released a hearty aroma.

Better: He pushed on the front door and released a hearty aroma. What kind of food was she cooking?

Example 2: He saw orange lanterns, lights, green umbrellas, and heard the music of violins when he crested the top of the hill.

Better: When he crested the top of the hill, orange lanterns illuminated the twilight. Green umbrellas rose up from cozy tables. All around, the music of violins created a sweet harmony.

Commas and Compound Sentences

Next, let’s make sure we examine comma usage and compound sentences. The best way to do this is using the following mnemonic: FANBOYS, for “for,” “and,” “nor,” “but,” “or,” “yet,” and “so.” When using one of the FANBOYS words to combine thoughts, this forms a compound sentence. Comma placement is commonly seen after the conjunction word. Or neglected. In short, it’s rarely in the right place. The simple rule: Break the sentence at the conjunction. If they form two separate sentences, a comma is mandatory. The comma comes before the conjunction.

Example 1: I went to the party and ate until I was sick. Break it: I went to the party | ate until I was sick

The sentences cannot stand by themselves as two separate sentences. Therefore, a comma is not inserted.

Example 2: I went to Johnny’s and I fell in love at first sight with the puppy on the stoop.

Break it: I went to Johnny’s | I fell in love at first sight with the puppy on the stoop.

Both are single separate sentences and can stand by themselves. Therefore, a comma is required: I went to Johnny’s, and I fell in love at first sight with the puppy on the stoop.

Basic Passive Voice

Passive voice can almost always be identified with “-ing” words, especially when used with a “to be” verb. But “- ing” isn’t the problem. It is the was + “-ing” form of passives that is the problem. Nix the structure, and use the straight past form of “-ed.”

Example:

Don’t eliminate every use of “was”—it is often necessary. Eliminate occurrences of “was” + “-ing.” Unless your entire story is written in present tense.

Basic Gerund Issues

Virtually anytime “-ing” occurs, it is a gerund structure. And these can lead to gerund conflict. One way to check for conflict is a very simple method. Ask yourself, “Can the action be done at the same time?”

Example 1: Smiling, he answered the phone.

Yes, these two actions can take place at the same time. This is an okay structure.

Example 2: Running around the chair, he entered the back lawn.

No, you cannot run around the chair at the same time you enter the back lawn. One action comes before the other. This structure is incorrect.

More examples:

Having finished the assignment, the TV was turned on.

He was walking across the room with his shoes off.

He walked across the room with his shoes off.

Correct: Having finished the assignment, Jill turned on the TV.

Having arrived late for practice, a written excuse was needed.

Correct: Having arrived late for practice, the team captain needed a written excuse.

In both examples, the doer of the action must be named correctly in the sentence. Dangling modifiers modify words not clearly stated in the sentence.

Dangling Modifier Issues

Comma usage is frequently an area where writers struggle. Another common comma issue is dangling modifiers. The action set apart in commas must relate to the subject that is making the action.

Example 1: Having been born with three legs, it is obvious the cat struggled with balance.

In this example, “having been born with three legs” modifies the pronoun “it.” But what it is supposed to modify is “the cat”. Therefore, it needs to be adjusted:

Example 2: Having been born with three legs, the cat struggled with balance.

Example 3: Wanting something warm and cozy, the colorful quilt gave the cat a place to sleep.

The clause before the comma modifies “the quilt,” when the intended recipient is “the cat.” Rearrange the sentence:

Correct: Wanting something cozy, the cat fell asleep in the colorful quilt.

Repetition

As you go through your book, if you didn’t on the read- through, be sure and note words and phrases you repeat a lot, especially on the same page. Make a list and go back and ask yourself the following questions: Is the word really necessary? If it is, what are other ways to say the same thing? Then adjust accordingly. While repetition as a tool for emphasis is valid, unintentional repetition can become annoying and distracting. Nothing stands out to readers more readily than constant repetition. So eliminate as much as you can.

Dialogue Tags

When you have finished the tips I just provided, go back and review your dialogue tags using the tips I offered in my post on How To Use Speech Tags Well.

For more on self-editing, come back next Wednesday. For more WriteTips, click here.

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is a national bestselling author/editor and Hugo-nominee who’s edited over a dozen anthologies and hundreds of novels, including the international phenomenon The Martian by Andy Weir and books by Alan Dean Foster, Frank Herbert, Mike Resnick, Angie Fox, and Tracy Hickman as well as official entries in The X-Files, Predator, Joe Ledger, Monster Hunter International, and Decipher’s Wars. His debut novel, The Worker Prince, earned honorable mention on Barnes and Noble’s Year’s Best Science Fiction. His adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction books have been published by publishers such as St. Martins Press, Baen Books, Titan Books, IDW, and more. Find him online at his website bryanthomasschmidt.net or Twitter and Facebook as BryanThomasS.

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is a national bestselling author/editor and Hugo-nominee who’s edited over a dozen anthologies and hundreds of novels, including the international phenomenon The Martian by Andy Weir and books by Alan Dean Foster, Frank Herbert, Mike Resnick, Angie Fox, and Tracy Hickman as well as official entries in The X-Files, Predator, Joe Ledger, Monster Hunter International, and Decipher’s Wars. His debut novel, The Worker Prince, earned honorable mention on Barnes and Noble’s Year’s Best Science Fiction. His adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction books have been published by publishers such as St. Martins Press, Baen Books, Titan Books, IDW, and more. Find him online at his website bryanthomasschmidt.net or Twitter and Facebook as BryanThomasS.

To download How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction free one book, click here.

To check out Bryan’s latest novels, click here.

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 12: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends, the first of three parts in a series covering Beginnings, Middles, and Ends. To see part one, Beginnings,

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 12: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends, the first of three parts in a series covering Beginnings, Middles, and Ends. To see part one, Beginnings,  The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 12: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends, the first of three parts in a series covering Beginnings, Middles, and Ends. To see part one, Beginnings,

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write a Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction Chapter 12: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends, the first of three parts in a series covering Beginnings, Middles, and Ends. To see part one, Beginnings,

Diction and Dialect

Diction and Dialect ["I function ninety percent like a human being in most respects," Lucas said as they continued up the stairs.

"Yeah, and at least ten percent is how you talk," Simon teased.

Lucas turned a puzzled look at him. "You think I do not speak like a human?"

"No normal human uses the cadence you use, no," Simon said.

Lucas looked disappointed. "Well, I hope you will assist me to do better. I am designed to blend in with humans and wish to learn."

"You want to blend stop saying things like 'in most respects' or 'I am designed,'" Simon said, shaking his head. "You sound like a machine."

Lucas hrmphed. "I will remember."

["I function ninety percent like a human being in most respects," Lucas said as they continued up the stairs.

"Yeah, and at least ten percent is how you talk," Simon teased.

Lucas turned a puzzled look at him. "You think I do not speak like a human?"

"No normal human uses the cadence you use, no," Simon said.

Lucas looked disappointed. "Well, I hope you will assist me to do better. I am designed to blend in with humans and wish to learn."

"You want to blend stop saying things like 'in most respects' or 'I am designed,'" Simon said, shaking his head. "You sound like a machine."

Lucas hrmphed. "I will remember."  Here’s an example from my novel The Worker Prince:

Here’s an example from my novel The Worker Prince: Remember that characters may speak differently to one character than another depending upon their relationship, their motives, etc. If hanging with old friends from the old ghetto, one may slip into a dialect left behind in childhood for those interactions even if the character usually speaks in a more refined way with characters outside that world and life. Ever have a friend from a foreign country or the U.S. Deep South who talks with one accent with you but goes home and slips back into a native accent? People speak to a lover different than a mother or a sister or a boss or a priest. One also speaks differently to a king or ruler than a fellow citizen and often to a teacher than fellow students, and so on. So remember to establish changes in dialogue appropriate to the circumstances in which the dialogue is occurring and who and to whom the characters are speaking. This will make your world come alive and feel realistic.

Remember that characters may speak differently to one character than another depending upon their relationship, their motives, etc. If hanging with old friends from the old ghetto, one may slip into a dialect left behind in childhood for those interactions even if the character usually speaks in a more refined way with characters outside that world and life. Ever have a friend from a foreign country or the U.S. Deep South who talks with one accent with you but goes home and slips back into a native accent? People speak to a lover different than a mother or a sister or a boss or a priest. One also speaks differently to a king or ruler than a fellow citizen and often to a teacher than fellow students, and so on. So remember to establish changes in dialogue appropriate to the circumstances in which the dialogue is occurring and who and to whom the characters are speaking. This will make your world come alive and feel realistic.