The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 2:

The following is an excerpt from my book How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, Chapter 2:

A sketch that will inform your outline, the three-act structure nonetheless identifies the core dramatic points of a story. Some of you may be discovery writers like me, preferring to let the story unfold organically. But at some point, you will be required to outline as a professional writer. And when faced with a tight deadline, the more organized you are, the more efficient you can be. The first thing you need to do is understand the dramatic structure that underpins your story. So we are going to talk about a very simple, basic way to identify key points that can help you write more quickly and efficiently to meet a deadline.

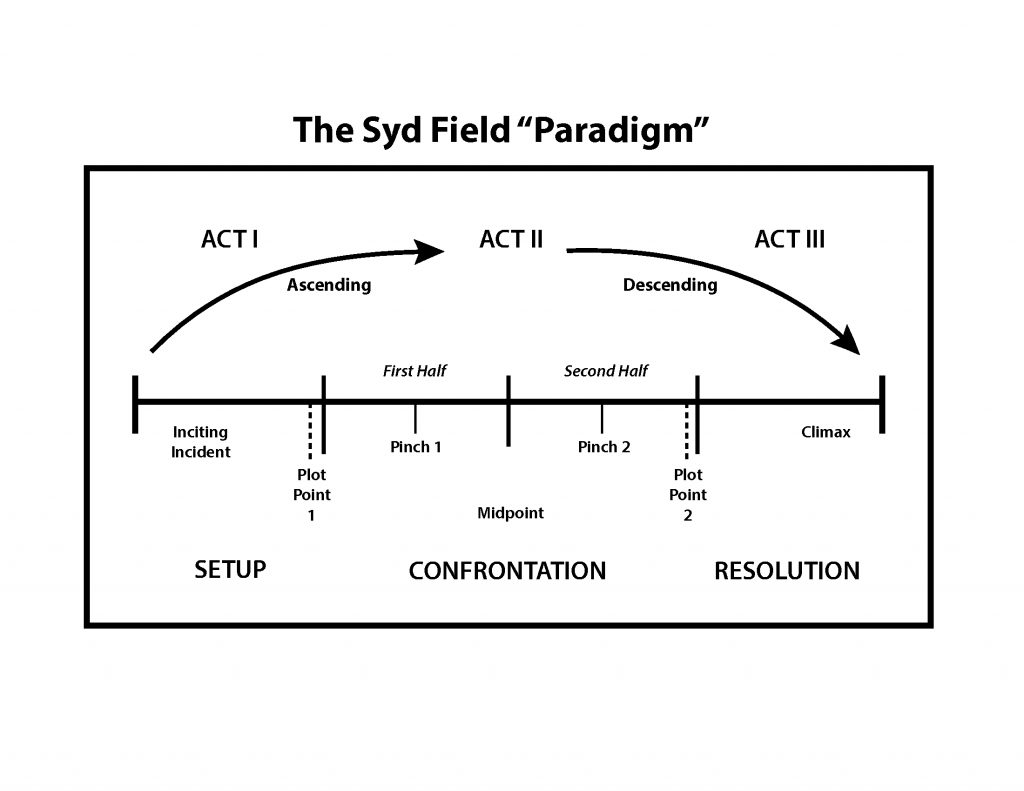

While outlines are multiple pages of detail, the structural diagram will be no more than a brief paragraph or a few sentences describing each required point accompanied perhaps by a paradigm sketch. The paradigm shown is based on Screenplay by Syd Field, a classic writing teaching book employed by many film schools, but in Western literature, the principles also apply to any dramatic story, including those told in prose. The outline is for three acts. In a screenplay, those are act one, which is 30 pages, or a quarter of the text; act two, which is 60 pages, or half; and act three, which is 30 pages, or a fourth. Your page numbers will vary, but the fractions for each portion should wind up roughly the same.

The key turning points between acts are called plot point 1 and plot point 2. These are events which force the protagonist, and sometimes the antagonist too, to turn in new directions and take new action in pursuit of resolving the conflict. Plot point 1, at the end of act one, will require agency, or action, from the protagonist in pursuit of finding the solution and determining what must be done. Plot point 1 propels the protagonist into act two, which is an ascending action involving discovery and a journey to find the solution and achieve the goal without yet knowing all that is required. In the course of act two, the questions will be answered until you reach plot point 2. Plot point 2, at the end of act two, will occur when the protagonist discovers what must be done and where, and with whom, to resolve the conflict and achieve the goal. And thus, it propels him or her into act two, which is the climactic, descending action to reach that point.

The key turning points between acts are called plot point 1 and plot point 2. These are events which force the protagonist, and sometimes the antagonist too, to turn in new directions and take new action in pursuit of resolving the conflict. Plot point 1, at the end of act one, will require agency, or action, from the protagonist in pursuit of finding the solution and determining what must be done. Plot point 1 propels the protagonist into act two, which is an ascending action involving discovery and a journey to find the solution and achieve the goal without yet knowing all that is required. In the course of act two, the questions will be answered until you reach plot point 2. Plot point 2, at the end of act two, will occur when the protagonist discovers what must be done and where, and with whom, to resolve the conflict and achieve the goal. And thus, it propels him or her into act two, which is the climactic, descending action to reach that point.

When I write any story, I always start with some idea of what my plot points will be and how it will end, to give me a sense of focus and direction as I write, even when allowing it to unfold organically. Now, just as the overall story has three acts, so will each plot and subplot, and each act. As such, each has a mini turning point called the midpoint or pinch that twists the action a bit and propels us into the second half. In the first act, this is called the inciting incident. This inciting incident often provokes a change in the protagonist’s routine—something new they experience that could either challenge or encourage them. In The Silence of the Lambs (1991), FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) meets with Dr. Hannibal “the Cannibal” Lecter (Anthony Hopkins). The confrontation of both parties is nerve-wracking. But it intrigues us and sucks in Clarice and leads to the rest of the story. Other examples are Indiana losing the golden idol to Belloq at the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark, which then sets up a rivalry that drives the later journey as Indiana Jones seeks to get the Ark before Belloq. Morpheus choosing Anderson in The Matrix sets up all that follows after. In The Sixth Sense, without the opening confrontation and gunshot, nothing else that follows could occur.

When I write any story, I always start with some idea of what my plot points will be and how it will end, to give me a sense of focus and direction as I write, even when allowing it to unfold organically. Now, just as the overall story has three acts, so will each plot and subplot, and each act. As such, each has a mini turning point called the midpoint or pinch that twists the action a bit and propels us into the second half. In the first act, this is called the inciting incident. This inciting incident often provokes a change in the protagonist’s routine—something new they experience that could either challenge or encourage them. In The Silence of the Lambs (1991), FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) meets with Dr. Hannibal “the Cannibal” Lecter (Anthony Hopkins). The confrontation of both parties is nerve-wracking. But it intrigues us and sucks in Clarice and leads to the rest of the story. Other examples are Indiana losing the golden idol to Belloq at the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark, which then sets up a rivalry that drives the later journey as Indiana Jones seeks to get the Ark before Belloq. Morpheus choosing Anderson in The Matrix sets up all that follows after. In The Sixth Sense, without the opening confrontation and gunshot, nothing else that follows could occur.

In act two, you have a pinch point for each half, and in act three, you have the climactic confrontation before the denouement. These may not be as dramatic as the inciting incident of act one, but they nonetheless inspire the protagonist or antagonist to take further action and move forward on the journey. Whereas the plot points are both major dramatic developments, the inciting incident, midpoint, and pinches can be more internal than external but of significance to the characters’ hearts and minds such that they cause them to change course and move in a new direction or with renewed vigor toward the goal. These are like lesser plot points, in a way, but nonetheless significant points in the framework of the overall dramatic arc that drives your story.

Let’s talk examples. In Star Wars: A New Hope, the inciting incident starts with Darth Vader’s ship attacking Princess Leia’s rebel ship and forcing her to load the Death Star plans into R2-D2, the droid, and send him to escape. He lands on the planet with his companion, C-3PO, and they wind up in the hands of the hero, Luke Skywalker. When Luke discovers a message from a princess that reports danger and points him to a mysterious figure named Obi-Wan Kenobi, he sets off to find out what it means, and that leads him to Old Ben Kenobi, whose shared surname is an obvious clue. Kenobi rescues Luke from Sand People at the midpoint of act one and takes him back to his own home. There, they view the message and Kenobi gives Luke a lightsaber and tells him about the murder of his father, a story Luke never knew. The Empire and a Rebellion, which until now have been mostly rumors far away, have entered Luke’s life, and when Kenobi takes him home, they find that the Jawas who sold Luke’s family the droids have been murdered and torched. Fearing the worst, they race to Luke’s home and find Luke’s aunt and uncle have been murdered and their homestead torched. Plot point 1 is when Kenobi tells Luke they must go rescue the princess together and find a way to deliver the plans hidden in R2-D2.

Act two starts with their trip to Mos Eisley spaceport where they must find passage, and they end up recruiting Han Solo, evading Stormtroopers searching for the droids, and head off for Alderaan. Then, we see Luke in training for the inevitable confrontation, while Vader and Tarkin attempt to extract information from Leia, and ultimately destroy Alderaan. Luke, Han, and Kenobi’s discovery of this is our pinch point for act one. That determines they must rescue Leia themselves and deliver the plans. Then they are caught in a tractor beam and pulled aboard the Death Star. The midpoint comes during the attempted rescue in the Detention Block when they are trapped. The pinch point for act two is when Kenobi confronts Vader to help his friends escape with the droids to the rebellion. Plot point 2 is after they fight their way clear and escape to the rebel base, where the plans reveal the Death Star’s flaw. The Rebels unveiling their attack plan propels us into act three. Act three is the Rebel attack and the Imperial counterattack, and the climax comes as Luke faces off against Vader in the trench run and ultimately destroys the Death Star with surprise help from Han.

So, now that we have seen how this plays out in a story we are all familiar with, it’s time to identify this structure for your story. Keep in mind that this is only a blueprint. Plans can change. As the story evolves, if required, your plot points, as well as pinches and midpoints, and even your climax, may change. The point of this is not to set anything in stone but to have goals to guide your work. It will help direct you as you write and set up each character and point required to reach each marker. If that ultimately requires the markers to change, it’s okay because these are tools to help you achieve a whole.

Here are the things you’ll need to know to develop this paradigm outline.

Who is your protagonist?

Who is your antagonist?

What are their goals?

What are the obstacles each faces in reaching that goal?

What growth must each undergo to make success possible?

And finally, what do you think the final confrontation needs to be?

Answering these questions is just a temporary means to an end. The answers may change, but the idea is to think through key elements of your story to allow you to write with blinders off and have some goal points along the way to work toward. That will allow you to write faster and spend less time wondering what the heck you should do next. As you actually write, these goal points may need to change, and that is okay.

To download a free copy of How To Write A Novel: The Fundamentals of Fiction, click here.

Tomorrow: Part 2-4 Act Structure

Friday: Part 3-How To Structure Scenes

For these and other WriteTips, click here.