NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful.

NOTE: This is a reprint of an old post which wasn’t a WriteTip but should be. Still relevant. Hope it’s useful.

In the current climate of instant everything, protecting your work is important. Anything you post online or email to a friend could potentially be stolen. So how do you protect yourself? One important method for serious creatives is by copyright. Now copyrighting is handled by the Library of Congress a Federal agency. It’s not the best approach in all cases, because it’s not inexpensive. At a cost of $35-65 per written work, that can really add up. But it does provide security. By law, copyrights last the author’s lifetime plus 50 years and can be renewed indefinitely by legal heirs. You’re also listed and a copy kept on file in the archives at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. which can be used as evidence in legal proceedings should you face the misfortune of having to sue to protect your intellectual property. So there are advantages to this but it may not be right for you in every case. Much information can be found on the Library of Congress sites at www.loc.gov and www.copyright.gov.

By law, Copyright exists from the moment of creation. So protections are already in place under the law. However, registration of copyright can be important in providing stronger proof and enabling you to sue for more damages in the case of infringement. This post examines how to go about officially registering a copyright claim and when it might be a good idea to do so.

How To Determine If Copyright Registration Is Necessary:

1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.

1) Is your creative work at risk? If you post it online, the answer is yes. If you turn it in as a class assignment, the answer may be no. Most professors would never violate your copyright. And in most cases, when you are first learning, school work isn’t going to have serious potential for marketing. So the likelihood of your work being stolen and distributed is pretty minor. What is the intended audience and how is the work being distributed? If your work is really at risk, then copyright may be a good idea.

2) What is the type of prose? If it’s fiction, poetry, or nonfiction on a significant topic, copyright is wise. But how do you know it’s significant? What’s the subject? If it’s scientific with unique contributions to the study of the topic, involves a subject of great interest (celebrities, political issues, religion, etc.), then perhaps it’s worth copyrighting. Some raw scribbles, probably not. It’s up to you to determine and in this day and age, caution should be the watch word, but do use wisdom.

3) Do you own it? If your work is a work for hire, you have no right to claim it. A work for hire is a creative work instigated by someone else but created by you on their behalf. In most cases, your contract stipulates that they own all rights. If not, that should be worked out. If you are writing technical manuals for a product owned by a company, the copyright will belong to them. If you are creating something original from your own mind for them, that’s another question. But you must own a work to claim the copyright. If your work is derivative of another property, such as a Star Trek tie-on novel, you likely cannot copyright it. If you can, you can only copyright the original portions which were not previously created by the originator.

4) Is Your Work Valuable? If you are just an unknown person posting on a blog, putting copyright notice (c) on the blog itself should protect you. The law states that your copyright is owned by you the moment you publish the work and suggests putting appropriate notice. Registration through the Library of Congress is merely a formality for extra protection in court or legal matters. It’s a way to prove definitively that your claim is valid. If you are a celebrity or you work will be significantly distributed, then the chances are it will come to be of such value as needing extra protection.

Once you’ve determined that it’s appropriate to register a copyright, then you need to get the materials necessary together.

What You’ll Need:

1) A clean copy of your manuscript--Typed for clarity is best. And make sure it’s the version you want to protect. Do all editing and other adjustments. Formatting itself is not copyrighted, only content, so layout is not the concern, just the content itself. Also be sure and put your name, address, phone number and other relevant information, including a copyright notice on the work. Don’t put a date as that won’t be official until you actually file.

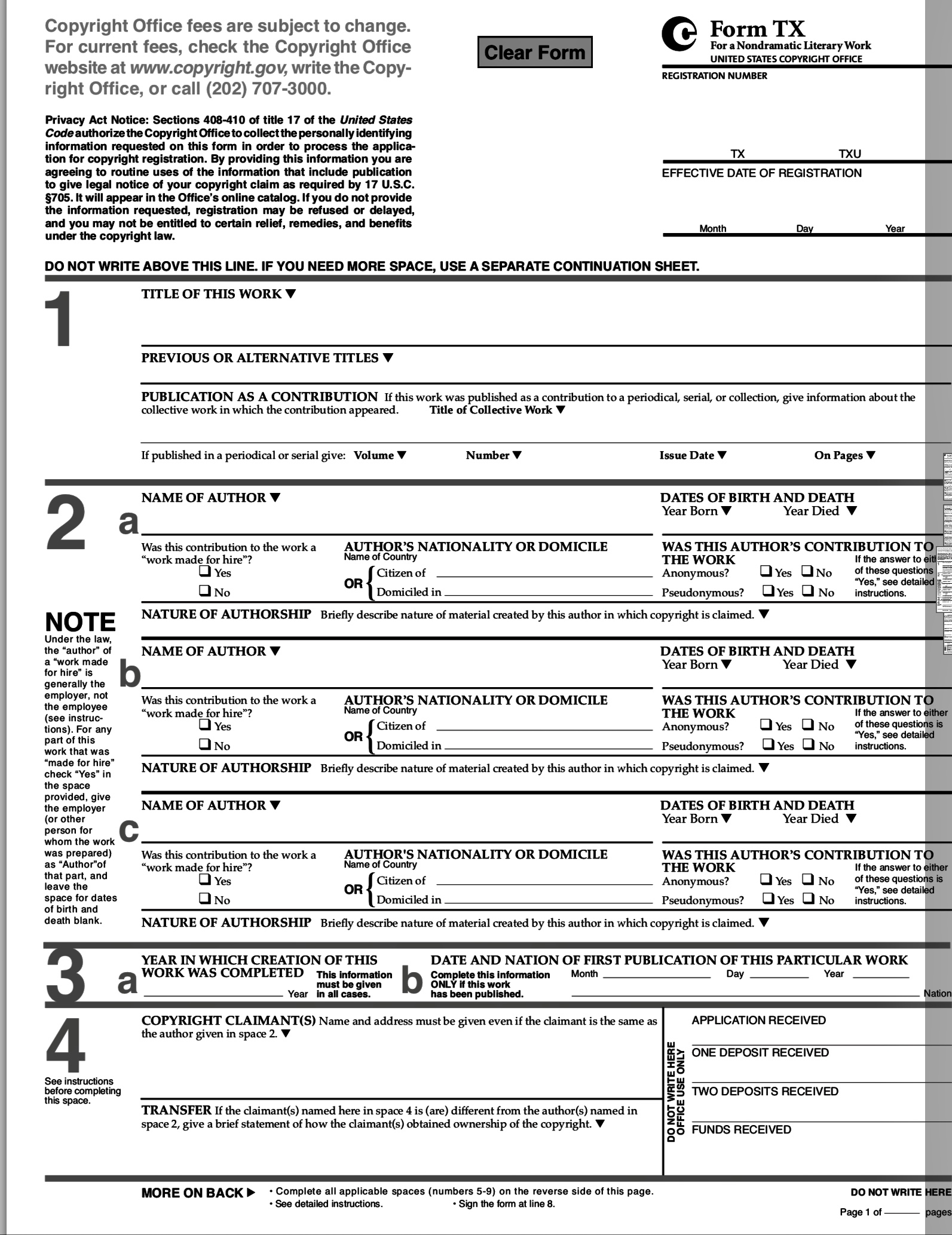

2) Form TX–the official copyright form, which can be found here: http://www.copyright.gov/forms/formtx.pdf

3) A check or credit card–to pay the filing fee which is currently $35 online and $65 by mail.

4) A stamped envelope–if you intend to mail your submission.

Once the materials are ready, then you can file as follows:

1) Fill out the appropriate form in detail. List all pertinent information as concisely and clearly as possible. Be sure and save a copy of the form for yourself in case it 1) gets lost in the mail; b) you need it for reference, etc.

2) Paperclip the form to your work and place in envelope. Mail it. No need for Priority, Registered or Express or tracking. All of these cost extra. You will get confirmation that it’s been received by mail when your copyright certificate arrives. However, if you have the money and want reassurance, you can pay for these as you wish.

To file online,

1) Find the Electronic Copyright Office online at: http://www.copyright.gov/eco/ and register yourself. Read the relevant information about acceptable file types, etc. When you are ready, fill out the form here: http://www.copyright.gov/eco/help-registration-steps.html

2) Once the form is filled, attach your document. You will be prompted. Again, view the list of acceptable file types above to verify yours will be accepted in its present format.

3) Make electronic payment. This can be done online with credit or debit card or electronic check and you will be prompted.

4) Submit. Click the button to submit when you are finished.

Processing time can vary, and the Copyright Office site issues the following warning:

The time the Copyright Office requires to process an application varies, depending on the number of applications the Office is receiving and clearing at the time of submission and the extent of questions associated with the application.

Like everything else in life and especially when dealing with government, you will have to wait, but you will receive a copy back of your registered form signifying recognition and acceptance of your claim with the official date of copyright. This can be kept in a safe deposit box or file.

That’s it. Allow a few weeks for a record of your copyright to be searchable in the Library Of Congress database. But you can rest assured you will soon have a legally registered copyright protection for your work.

An example of a listing can be found here. I own several copyrights to musical works as listed. Not everything under “Bryan Thomas Schmidt” is mine, however.

I hope his helps you better understand the copyright process.

I have never written fanfic and I long ago stopped even attempting to read it. Like many, I sought out fan fiction as a way to get more time with characters and in worlds I’d fallen in love with. My hopes were high for a new escape and recapturing all the emotions I felt when I read the original. Unfortunately, I found that most fanfic is a poor imitation. Are there talented writers writing fanfic? Yes. But it’s not my point that no talent exists in the pool. Some even practice their craft and develop it writing that. I get it. But from quality and style to plotting and other factors, a majority of it, in my experience, just isn’t the same, and, frankly, all too much of it was just not good at all. But on top of that, I always had doubts because of an inner belief that it’s not legitimate. And although I’ve not written anything popular enough to inspire such imitation, I’ll respond as if I had, because this is pretty much how I’d feel if it happened that way.

I have never written fanfic and I long ago stopped even attempting to read it. Like many, I sought out fan fiction as a way to get more time with characters and in worlds I’d fallen in love with. My hopes were high for a new escape and recapturing all the emotions I felt when I read the original. Unfortunately, I found that most fanfic is a poor imitation. Are there talented writers writing fanfic? Yes. But it’s not my point that no talent exists in the pool. Some even practice their craft and develop it writing that. I get it. But from quality and style to plotting and other factors, a majority of it, in my experience, just isn’t the same, and, frankly, all too much of it was just not good at all. But on top of that, I always had doubts because of an inner belief that it’s not legitimate. And although I’ve not written anything popular enough to inspire such imitation, I’ll respond as if I had, because this is pretty much how I’d feel if it happened that way.